Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Behind the Reece Act

By Nick Martinez/Photos by Luke Montavon

On Sept. 2, 2002 Reece Nord was riding his bike home when he was stuck and killed by a drunk driver. The driver, Justin Mishall, was later charged with several counts, including vehicular manslaughter, and served 3 1/2 years in prison. Part of his sentence was also to pay restitution to the Nord family $15,390 for medical and funeral costs. More than a decade later, Mishall has paid $750 of the total sum he owes.

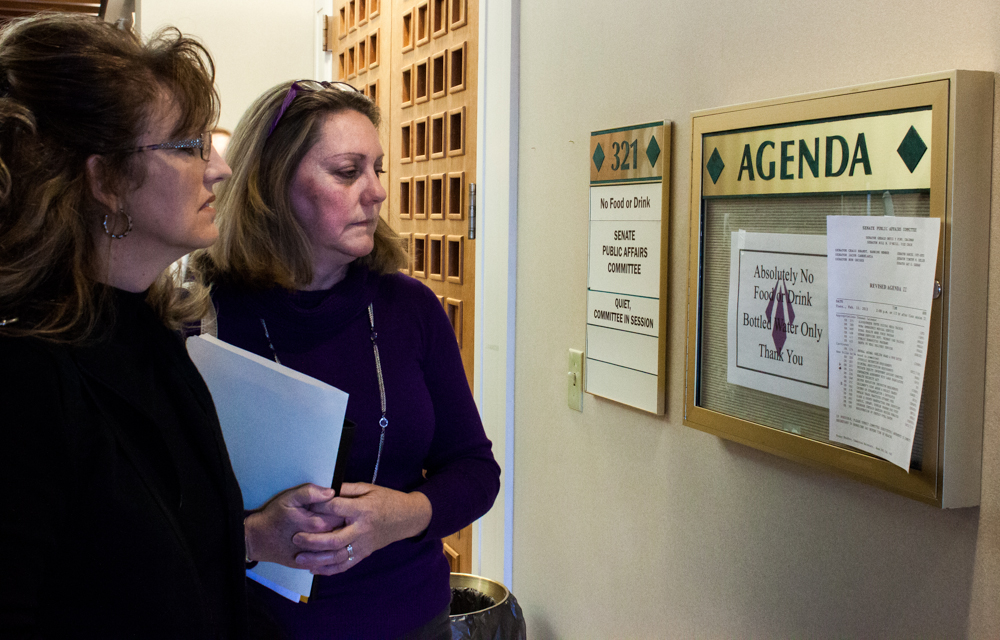

Witness’s Cindy Chapman (Aunt, Left) and Barbara Nord (Mother, Right), await to testify before the Senate Committee.

Due to a loophole in New Mexico law, once a criminal completes his or her parole they no longer have to legally pay the restitution the courts originally demand that they pay. Families can take these criminals to civil court, though that brings plenty of expenditures on its own

Nord’s family, not wanting to deal with Mishall any longer, penned a letter that eventually reached Gov. Susanna Martinez, who made sure that a bill was drafted. State Sen. Mark Moores, R-Bernalillo, sponsored the Criminal Restitution Act, also known as The Reece Act, which was recently tabled until the next legislative session.

“The current loophole lengthens the criminal process, it causes more expense to the family because they have to hire another attorney,” said Moores. “It just clogs up our court system with these civil lawsuits.”

While the civil courts may be clogged, the financial report regarding SB 207 indicates that the judicial courts don’t currently have the resources to support tracking down defendants who refuse to pay restitution, and providing those resources may prove too costly.

With the state unwilling to pay, it leaves the family in charge of tracking down their restitution, prolonging their relationship with the people who wronged them. This prolongation is exactly what Barbara Nord, Reece’s mother, is trying to avoid.

“I don’t want to deal with him for 25 years of my life,” said Nord. “We want the courts to come in and enforce the law.”

With lawyers advising their clients to refuse to sign any intention documents as their parole comes to a close, there is no way to enforce the current law.

In the Nord family’s case, even if the bill were passed, they still wouldn’t receive a dime from Mishall due to the fact the law won’t apply retroactively. It is good enough for them if no other family has to go through the same ordeal.

“It’s taken years, and years, and years to try to get the family back where everyone’s functioning normally,” said Nord. “Maybe this isn’t even normal, there is no normal, normal is gone.”

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.