Tags

Related Posts

Share This

The Screen Goes Digital

“It’s all George Lucas’ fault,” says Peter Grendle, the Screen’s cinematheque manager, dispensing news of the world’s steady conversion of film projection to digital projection. According to Grendle, when director George Lucas filmed the last of his famous Star Wars episodes from 2002-2005, he loathed the idea of his precious turn-of-the-century movies going up on what Grendle calls the “shitty mall theaters” (whose projectionists pay little attention to presentation). Determined to get the best possible picture, Lucas shot Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith in 100 percent high definition and premiered them in select theaters using digital projectors. Even if the mall theaters failed Lucus, at least the final prequels were forever in high definition.

Since then, filmmakers have followed George Lucas, the “father of digital cinema,” into the inevitable future of digital. Hence, the annihilation of film! That’s a bit dramatic. Hence, movie company’s slow change from film to affordable new age cinema. And, for better or worse, the Screen, part of the 10 percent of theaters still capable of 35mm film projection, has finally gotten the boot: its 35mm projectors are retiring. A digital cinema package (DCP) will take their place.

“We’ve been essentially an all blue ray theater for the past year,” Grendle says, “we do as many 35mm [films] as possible…but we have to [install] digital if we actually want to play movies. Otherwise the theater is just a place with, you know, great seats and a white wall.”

Expert projectionist Barbara Grassia believes that the Screen’s transition is a positive change because “digital’s visual quality has been improving.” Grassia has participated in Film Festivals such as Sundance, Tribeca, Traverse City, Bermuda, the Dominican Republic, Telluride, Turner Classics, and Durango Independent Film Festival. “While the quality of 35mm presentation has been steadily declining,” Grassia says, “many multiplexes have allowed 35mm equipment to deteriorate to the point that presentation is seriously compromised.”

Center for Contemporary Arts (CCA) Director Jason Silverman, who recently converted CCA’s primary film projection theater to digital, also points out that “DCP is pristine start to finish. Audio and picture quality are easily adhered to the filmmaker’s and studio’s intentions and we’re finding lots of interesting DCP content to show.”

The creator and curator of the Screen, Brent Kliewer, agrees that “the benefits [of digital] will far outweigh anything negative.” He adds, “digital is where the industry is headed and to keep up we (meaning all independent theaters) must move forward.”

It’s been a long time coming for the Screen, Grendle explains. Three years ago he received a letter from Fox, the high budget movie company whose films the Screen doesn’t play anyway, informing theaters that the company will no longer make 35mm prints. From there, Grendle was badgered by numerous companies to switch earlier rather than later. What was the final blow? The big companies gave in. The Regal Cinemas, a major branch of movie theaters, upgraded last year and according to Grendle, once the “big guys” convert, it means everyone else will follow.

For a while, however, the 15 percent of film geeks, or independent filmmakers and theater owners, protested the digital conversion and treaded the pool of their financial difficult for the sake of saving film.

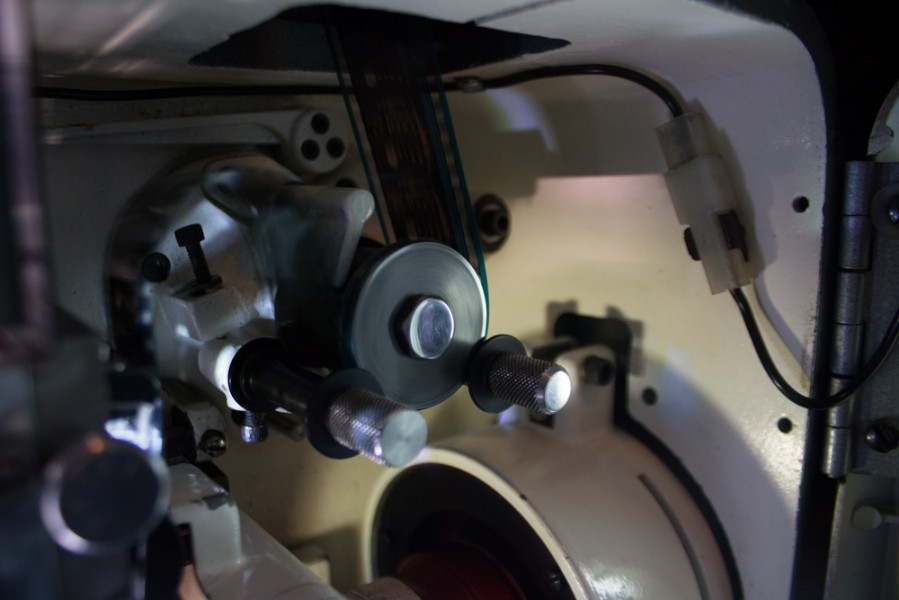

“All the indies are exactly the same,” Grendle says, “They’re pushing out these small weird art movies for a small weird art crowd in small weird art theaters.” He explains that the Screen, like the CCA and newly opened Jean Cocteau in Santa Fe, was founded on “a love for film.” Furthermore, Brent Kliewer, original founder of all three respected cinematheques, is himself a “film junky,” a believer in projection and acoustic perfection. The Screen, for example, was built on an old soundstage and the 35mm projector bulbs burn so bright that they’re moved away from the body of the projectors so the film doesn’t burn.

Regarding the art of film projection verses digital, Grendle won’t say that one is better than the other—“they’re just different,” he says. “They look different, they feel different. Film has flicker, grain and depth that I’ve never seen on the best 4k system…It’s kind of a kin to ‘do you like MP3s or vinyl records?’ We like vinyl records. They’re more vibrant, more alive. You feel like you can reach out and touch it.”

Barbara Grassia, who projected for the CCA for 7 years after coming to Santa Fe in 1987, says that one of her favorite things about working with 35mm prints was looking at “individual frames under a lupe (magnifier) and capture visually a 1/24th of a second still of the movie.”

“Whenever I’m projecting, it reminds me of the craftsmanship,” says Screen employee Stormy Lynn. “It’s a whole experience. The quality of film… it’s so raw, the color and light is organic and rich.”

“Film is analogue,” Silverman from CCA says, “received by the brain in a different way than digital. 35mm prints…have the visual equivalent to me, of a tactile quality. They’re living creatures. They are also often problematic to deal with. I have lots of stories, like any exhibitor, of last-minute rescues and heroic projectionists and shows that didn’t happen quite right but were excellent anyway.”

However, Screen employee Lynn points out that the average audience can’t really tell the difference between film and digital. “I think mostly [projectionists] can tell…because we stare at 35mm all day. We can actually see when film grain is real film grain.” Furthermore, the romance of film projection has not been enough to keep the independent movie theaters in business.

“35mm reels of film require a rigorous make-up process,” Kliewer says, “and a high-cost shipping, plus you have to have a full time projectionist.”

In order to appease the 15 percent of film geeks in the country, digital cinema initiatives summed up the benefits like this. 4k resolution matches 25mm, thus 2k kind of matches 16mm resolution. From the estimated $30,000 average cost of making film and $200 shipping cost, theaters would essentially save an annual $1 billion from the hard drive or satellite downloads, according to Amarillo Globe-News. Furthermore, the codes and registration of digital projectors would combat film piracy and provide the opportunity to show more films during the day.

“2k and 4k are really absolutely incredible in terms of quality,” Grendle admits and despite the costly transition of installing a digital system, the Screen on average would be saving the cost of projection salary, film shipping, and mechanical error of film projection.

The response of film geeks to the DCP offer, in the words of Peter Grendle, “ah shit, that’s kind of wonderful.” Though a bittersweet run for film, the Screen will install their recently purchased DCP in the end of October and become part of the new digital era of movie projection. For the future, Grendle assures, the Screen will still dedicate their venue for artistic and independent film companies and Brent himself promises that the 35mm projectors “will not be going anywhere. Part of our mission,” he says, “is to showcase archival prints and these will be shown in their original 35mm format.”

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments