Tags

Related Posts

Share This

The Surprises in Poetry

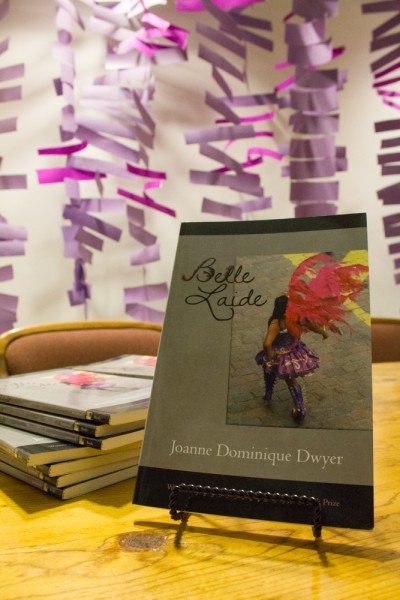

“Please don’t be too polite,” said Joanne Dwyer, after reading the first of several poems from her first book, Belle Laide. “I want poetry readings to have a little more life in them. Be yourself… heckle me a little!”

Before her reading began on Tuesday, Sept. 24 at SFUAD’s O’Shaughnessy Performance Space, Dwyer had admitted she was nervous, telling a friend that normally she spends “days and days and days not seeing anybody.” Once in front of the podium, however, she commanded the audience with a combination of humor, naked earnestness, and a reading voice that gave no sign of shaking.

Dwyer straddles these sorts of dualities— internal shyness and outward composure—in her writing as well as her life. On one hand, she loves the fragmentation and collage of poetry, the way that “words and how we string them together are our tools as writers.” The rules in poetry are different, Dwyer says, so she feels free to let “imagination reign free to create image, sound and tonality without the normal everyday mundane rules of language.”

At the same time, however, Dwyer admits that maybe the fragmentation and shorter form of poetry just matches her attention span better as a writer than fiction would. She loves reading fiction—making an effort to read Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude annually—but says that, “the idea of writing a plot is just terrifying.” Her poetry, she explains, does not look for a truth in the way that a novel might. “Sometimes,” she says, “even I couldn’t tell you what the hell it’s about—that’s the magic of poetry, but sometimes I wonder if it’s to my detriment as a writer, if I’m just hiding behind the language.”

Still, Dwyer is praised for her stream-of-consciousness and vocabulary-rich writing. She writes, says Creative Writing Co-chair Dana Levin, who taught Dwyer as a student at the College of Santa Fe, “in a way that tracks how the mind thinks. It is associative rather than linear.” Dwyer keeps this interesting by avidly reading up on everything historical, mystical and etymological that catches her attention and then working them into her poems. The mind, especially when its imagination is unfettered, is full of surprises. “The poetry that stays with me, that gives me an ecstatic juice,” says Dwyer, “is poetry that surprises me.” Dwyer both feeds and welcomes these surprises in her own writing by reading extensively, watching the world around her, and letting her own imagination string them together on the page.

Dwyer, a 2005 graduate of CSF in creative writing and literature, does not lament how little time she has to write like many writers do. A mother of two, Dwyer’s says that being a mother made her a better writer, and visa versa. She recalls hearing a quote from Toni Morrison in which she says that she has written novels and won prizes, but really she neglected her son. “This really surprised me,” says Dwyer, “because I think that when there’s tension in your life, and you’re really living in the real world at the same time that you’re creating, you fight harder for that creative time.”

When Dwyer began to feel that she’d spent enough time indulging in the reclusive act of reading and writing—for which she felt very lucky—she became involved in the Brooklyn-based Alzheimer’s Poetry project. “It just seemed like time to give something back,” she says. She would read poetry out loud to dementia patients in nursing homes, many of whom were losing their mental capacity for language. Dwyer found this process rewarding on many levels, and still makes regular visits to nursing homes around New Mexico.

“Some of them had to memorize poems when they were young,” she exclaims, “and they remember them when I start to read. The whole thing becomes a sort of call and answer.” The return to dignity—let alone language—that she sees in the elderly, who are often playing bingo or making crafts with glitter when she arrives, is more than enough to keep her returning.

Dwyer recently applied for and received a grant from the Witter Bynner Foundation to work with at-risk teens in Bernalillo—with poetry as her vehicle once again.

“I started to worry that I was getting too comfortable with people whose minds are compromised,” she says of her work with dementia patients, “and thought, ‘gosh, I wonder what it would be like to work with teenagers.’” Once again, Dwyer is taking on a situation that makes her undeniably nervous, but with the same gusto with which she agreed to hold a reading at SFUAD. “I just wanted,” she explains, “to do something that really frightens me!”

Whether or not Dwyer hides behind her elaborate strings of words and images, it is clear that her appetite to try new things and push herself into uncomfortable situations will continue to push her as a writer. “Mastery, the ability to separate yourself from your work enough to recognize what is good and what is not, is important,” says Dwyer, “but with complete mastery you miss out on all the surprising stuff that just kind of sneaks in there.”

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments