Tags

Related Posts

Share This

New Mexico Actually

In celebration of New Mexico Archives Month, on Oct. 2, employees of the State Records Center and Archives coordinated a special topic forum, “Documenting New Mexico’s Folk Traditions,” at The Screen. From lectures on witchcraft to a traditional New Mexico music performance, state historians uncovered and showcased some rich tales from the Land of Enchantment.

Presenters of the forum included NM land grant scholar Malcolm Ebright, State Historian Rick Hendricks and Assistant State Historian and musician Rob Martinez. Following the forum, Sibel Melik, senior archivist with a speciality in motion pictures, introduced the screenings of The Rattlesnake (1913) and Agueda Martínez: Our People, Our Country (1977), both NM-made film shorts that remain undistributed to the public but reserved digitally in the archives.

Though grateful to Brent Kliewer and Peter Grendle for use of The Screen, Melik admits that last year’s film screening was more attended by the public due to a 2010-2013 Preserve Grant which funded the preservation of additional NM films. This year, however, screenings were preceded by an exciting three-part panel.

Presentations began with “Concepts of Land Ownership in Colonial New Mexico,” the uncovering of court cases involving land disputes among early Puebloans and Spaniards. Historian Ebright, author of Four Square Leagues: Pueblo Indian Land in New Mexico, revealed that circumstance of today’s NM reservations stem from situations that the early Pueblo representatives, called protector de Indios, resolved after many trials and errors with the Europeans.

“The problem was they didn’t put anything in writing and that’s a lesson puebloans have learned,” Ebright says. A lot also depended on, for example, “skills of the advocate” and it was necessary, Ebright explains, for the Natives to adapt to Hispanic land management, like measuring by leagues and signing off on compromises and trade.

The second subject, popular in New Mexico folklore, was state historian Hendricks’ presentation on the history of witchcraft.

“When Spaniards came to the New World they transferred their traditional western notions,” Hendricks begins, aided by his illustrated projections.“This society [of colonial New Mexico], which was steeped in catholicism, was also very steeped in aspects of the supernatural.”

Despite this, Hendricks explains, the Spanish were baffled by the aboriginal practices of human sacrifices and what they termed “devil worship” and would later turn these practices into an excuse as to why Puebloans revolted against the Spanish in 1680. Hendricks mimics the possible scenario of a Spaniard who may have interrogated a Puebloan at the time saying, “the devil made you do this, didn’t he?” Hendricks adds, with irony, that “the Spaniards probably thought the [Pueblo Revolt] couldn’t have possibly been in reaction to colonialism.”

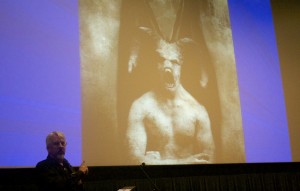

State historian Rick Hendricks displays what the Spaniards may have envisioned as the aboriginal “devil”

Because the tendency of the church was to label what they disapproved of as witchcraft, Hendricks goes on share that shamans and curanderas, a term used for Spanish healers, soon became a mass superstition in New Mexican society.

“We’re at a time when medicine is starting to emerge as a vast pharmacopia in New Spain,” Hendricks explains. “A lot of people and a lot of clergy, who tended to be more conservative and more scholastic in their thinking, were still suspicious of medicine in general. The idea that people, whether they be Indian or not, who could heal with plants were often suspected.”

The suspicion deepened especially when herbs were used in combination with Christian ritual, “which is something that became common especially as Indians became Catholic,” Hendricks says. “They would hold on to their ritual activities so you get this sort of fusion of Indian and Spanish.” This combination, Hendricks adds, would later feed the trade of medicine knowledge along the Rio Grande and continue to grow. Many of the traditional herbs are still used and available in New Mexico, and sometimes even preferred among non-natives to western medicine.

Concluding the panel, Rob Martinez, son of well-known corrido musician Roberto Martinez, sang and played his way through the history of New Mexican music. From the colonial period to the introduction of NM as a state in 1912, Martinez granted his songs with their native names and the situations in which they were sung.

For example, “La Delgadina,” a song brought from Spain about the injustice of a girl’s murder, was used in social situations; Penitentes, prayers sung by a brotherhood of the church, were used to ask for blessings; the albazo, an urban song-dance genre, was used for religious festivals; and various hymns were used to celebrate the relations between Spaniards and Puebloans. These songs, according to Martinez, acted also as chronicles, hence the term corridos, songs which preserve the history of a unique culture.

Lastly, this year’s two film screenings, archivist Melik explains, were intended to compare the outsider’s view of the state in the 20th century to the way it actually was.

Shot in Las Vegas as a silent film, The Rattlesnake was created by director, writer and actor Romaine Fielding who made at least 10 films in the town of Las Vegas, NM.

“Fielding was the biggest movie star you’ve never heard of,” says Melik. In 1913 he won the Motion Picture Story Magazine award for Best Photo Player, becoming popular in America as well as in Europe. In 1915, however, most of Fielding’s 200 films were destroyed in a fire, leaving four films intact. One was The Rattlesnake.

In this 15-minute short, an archetypical love triangle unravels with gunshots, rock slides, and the not-so-common snake bite! While protagonist’s sombrero and pancho wardrobe were not so common in Las Vegas at the time, the arroyos, mesas and adobe houses made up for the authenticity of the town.

Also not common, though strangely suiting, was the notion of a snake tamer being able to control a rattle snake. The relationship made between man and what traditional New Mexicans consider a demonic creature was maddening for the protagonist, who eventually had to choose to severe the supernatural ties in order to find peace and happiness.

The second film, a documentary on 77-year-old weaver Agueda Martinez, was chosen to showcase traditional New Mexican lifestyle in the early 20th century. A farmer, a mother, and an artist, Agueda lived off her farm in Medanales long after the passing of her husband and the move of her grown children. According to Melik, Martinez lived 25 years more after the documentary was made.

“We want to let people know we’re here and what we’re doing,” says Melik, describing her and her department’s goal in their annual presentations. The main purpose of these public and free events, Melik continues, is “preserving [NM] heritage and bringing…awareness of the archival collections.”

Melik and her fellow staff members even hope to take the archive presentations into Santa Fe’s elementaries and high schools in order to expose the stories to younger generations and perhaps even lure their families into a nostalgic journey of their home state.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments