Tags

Related Posts

Share This

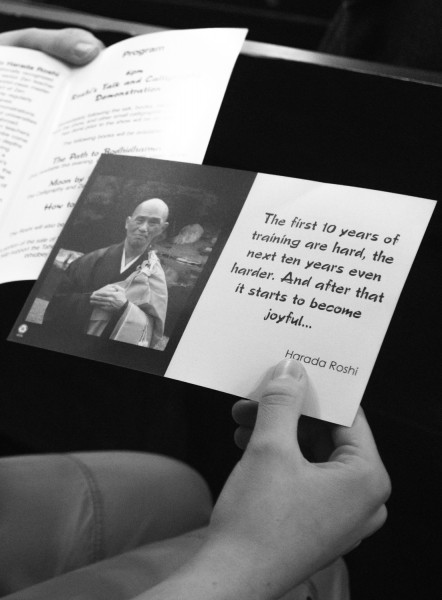

Night of Written Zen with Shodo Harada Roshi

By Charlotte Martinez/Photos by Natalie Abel

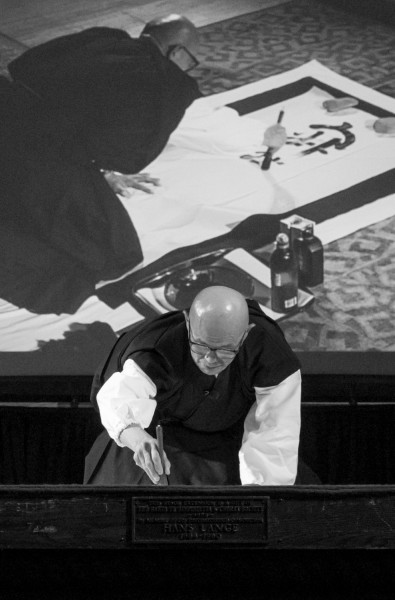

From the wall paintings on St. Francis’s auditorium in downtown Santa Fe, an image of the catholic saint gazes with pastel eyes at the scene forming in the front of his pews. Three robed members of the Tahoma One Drop Zen Monastery from Whidbey Island are seated on the stage, peering indifferently at the audience as they file in. A fourth member stands, monitoring a pile of blank canvases and a bowl of black ink on the stage floor. Positioned in front of these tools is at camera that projects the image on a large screen. This, no doubt, is for the convenience of those audience members who just hate when they can’t see.

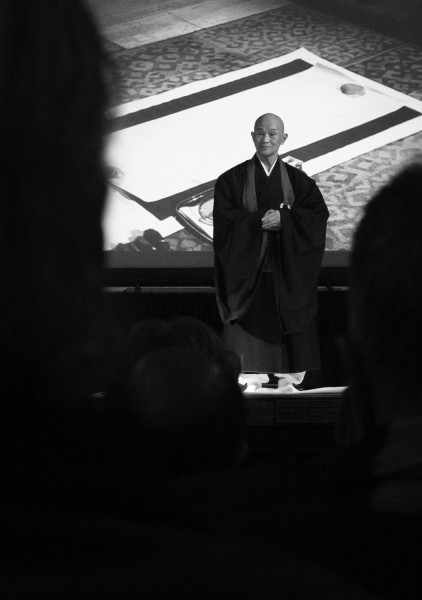

Japanese Master Shodo Harada Roshi stands on Francis’s stage with his hands clasped against his long black robe. He, like the others, looks serene and statuesque in what I can only label as a zen zone, but looking at the wise wrinkles and slick head I can’t help but calculate the master’s age. If he was born in 1940, his face is that of a 73-year-old, but even this doesn’t seem right. His face is too shaped and his posture too perfect; could this be a side effect of a disciplined life? If I feel like shaking his hand to obtain wisdom, is that too “western” of me?

His interpreter and facilitator, Daichi-Priscilla Storandt, sits next him with a kind-looking grin which contrasts the Roshi’s stoic one. If balance is essential in Buddhism, then the coupling is just short of perfect.

Books on the Roshi’s calligraphy works are for sale in front and I wonder if St. Francis objects to this display. The Roshi perhaps feels this too, and despite his title, practice and beliefs, the first thing the master does is pay his respects to the saint.

“I have visited Francis three times,” Storandt translates for her master, “I have been touched and moved by [his] life.”

Roshi’s deep voice flows in his native Japanese tongue and though most of us can’t understand, his words remain mesmerizing.

The way in which Francis lived, the Roshi continues, was by “not holding any personal possessions and living in a way of entrusting completely.” The Roshi shares his unusual routine of sprinkling ash in food when it’s too delicious and says that “Francis knew well…human beings are susceptible to infinite limitless desires.” He quotes the beatitude, “‘Blessed are the pure of heart for they shall see God.’ This way of purifying the mind,” he says, “is one of many points of how I live.”

His tribute to Francis comforts me. The siting of a beatitude is admirable in addressing a catholic culture, but it also made clear the buddhist concept of nirvana, the ultimate goal of a clear and wise mind. Somehow the mind is more universal than we predict.

“Everybody has times of being angry and being dark,” the Roshi explains. “It’s not easy to be in this place of a clear mind and for that purpose many different religions have held teachings sacred and important to be able to help us return to this clear mind.”

The Roshi’s eyebrows melt outward in empathy.

“We live in a world,” he says, “where we loose the person…most important to us…we are all subject to birth, sickness, old age, and death. There is no exception to this.” As he says this, the master extends his arms and opens his palms to the audience. Whether unconscious or not, the image of Christ radiates from his soft expression and long draped sleeves. This must be the time of revelation. The audience is silent.

“We all suffer from those days when can’t resolve this,” he continues, “if we can’t cut all that extraneous thinking that anger and that greed, then we get crushed by our emotions, that’s why we have to realize…that every day is a good day.”

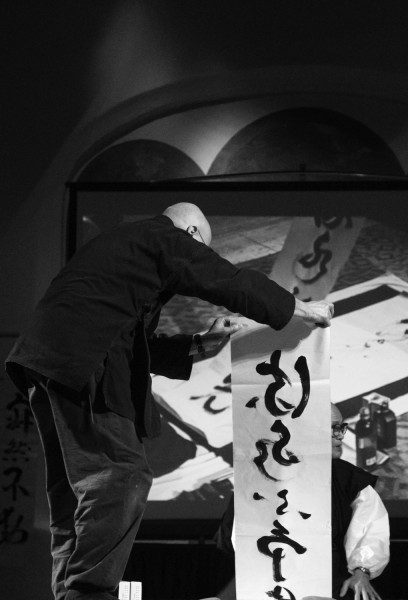

Appropriately, “every day is a good day” is the first Zazen phrase to be written in ancient calligraphy by Master Roshi. Pulling back his sleeves and settling on his knees, the Roshi dips his brush in his ink bowl and his arm extends in large swoops, small jerks, and calculated stokes down the parchment. As soon as the scroll is complete, a member of the monastery holds up the written phrase then hangs it behind the screen to dry.

“The serene mind is unmoved” is the next phrase, followed by “the clear mind is true teacher.”

As he writes, I wonder if there is anything left of the child Harada, the one who avoided the Buddhist priesthood of his father and dreamed of being a pilot. Do those years of meditation and enlightenment take away the individual? His calligraphy reflects this goal and I wonder how close nirvana is for him.

The audience sits wide-eyed, as if they’re watching Picasso paint a picture. They nod their heads or mumble with agreement when the phrases are recited aloud: “good fortune limitless as the ocean’s treasure,” “from the origin not one,” “watch your footsteps,” and many more.

His last calligraphies, called ensos, include the symbol of the infant universe, a simple circle within which “nothing is missing, nothing is extra.”

A little boy in the audience raises his hand.“Do you have to practice to make a perfect circle?” He asks. The audience laughs, but the master smiles and responds, “I’m often asked to make them.”

A question asked of the Roshi later regards his state of mind while writing.

“What is the relationship,” a woman asks, “between your hand, your mind and your heart?”

“I’m not paying any attention to my hands at all,” the Rochi says. “I’m seeing and becoming what I’m going to write next.”

The Roshi explains that the Zazen phrases “cut away extraneous unnecessary thinking. We are able to see from a huge spacious original mind, with which we are all endowed…becoming one with the heavens and earth.”

The Zazen scrolls hang now in a row behind the standing Roshi and the symbols look beautiful against Francis’s walls. I’m sure the saint would agree.

“My deep wish and vow,” the Roshi wraps up, is for “everybody [to] be able to experience the clear mind…we are what we think having become what we thought. When we hold joyful pure thoughts, our gladness will never leave us.”

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.