Tags

Related Posts

Share This

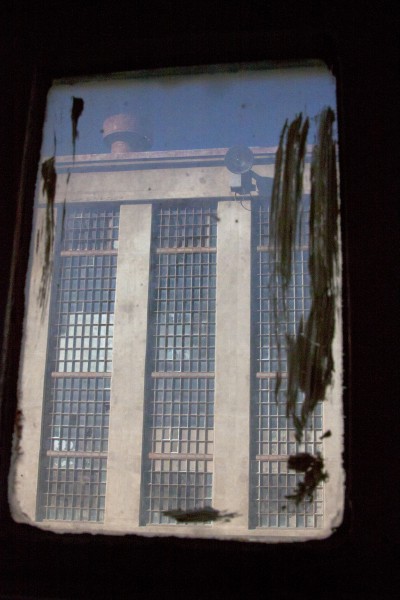

Walking the Old Main

The riot at the Penitentiary of New Mexico on Feb. 2, 1980 upended the world of corrections. Demands for better food, conditions and programming were forgotten as fury erupted from the residents. The reforms that came out of the event changed prison protocols forever. Now, the administration is embarking on a five-year plan to re-purpose the “Old Main,” which they discuss regularly with visitors on the prison tour.

Certainly, the events of the riot—captured vividly in numerous newspaper articles, state reports and books, continue to draw crowds. The guided “Old Main” tour slots have more than doubled due to demand and all ticket proceeds return to increase the quality of the tour and provide future programming for inmates. “Respecting our past to create a better future” is the motto the corrections officer acting as guide offers, before relaying the details of the riot.

In the early morning hours of Saturday, Feb. 2, 1980, inmates drinking a crude hooch overpowered the officer that discovered them. Soon, other officers within the dormitory were taken hostage and a set of captured keys liberated other inmates to ensure the riot would continue its course. These newly-freed inmates joined in beating Officer Juan Bustos, stripped and noosed with a belt, during the 12-minute march toward master control.

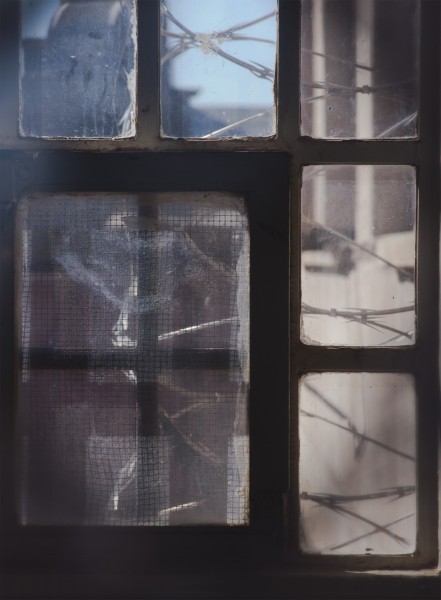

Nearly 100 inmates crowded in front of the newly installed bulletproof plexiglass window of master control. It shattered in three strikes from a fire extinguisher. The armory beneath master control was left undiscovered, limiting the extent of the carnage. Once the master control room was breached, approximately 2:02 a.m., greater access to the prison was attained.

Due to construction in cell block five, high risk inmates were mingled with the low risk population. The construction area housed numerous tools left by crews over the weekend. High risk inmates conceived an act of retribution against inmates in the protective-custody wing, which led to acetylene blowtorches, axes, drills and saws being used to gain access to cell block four, an area to which the rioters lacked keys. Thoughts of rescue at the hands of their fellow inmates turned to horror once the residents of cell block four—rapists, child molesters, informants and the mentally ill—were set upon by these tools. The slow gnawing of blowtorches on cell doors must have been excruciating for inmates awaiting their fate. Once the ritual of access proved too laborious, some inmates were simply immolated within their cells. Axe swipes marred the concrete floor entrance of cell block four—thought to be the site of a decapitation—a chilling reminder of the savagery that occurred. Some inmates not willing to participate in the riot fled into the freezing February air rather than partake in the unfolding atrocities.

The “Old Main,” as it became known, continued operation until 1998. Lessons learned during the 36-hour riot led to reforms in resident programming and care, as well as refined security measures. The “telephone pole” system, a central control method widely used at the time, has given way to a more compartmentalized “pod” system that houses controls limited to individual blocks. In addition, dangerous inmates requiring higher security are no longer mixed with lower risk inmates.

Tours of the Old Main connect the community to its past. Respectful—yet uncensored—these tours wind through the passageways of the Old Main, with file photographs from the immediate aftermath of the riot and informational tidbits that stick closely to the Attorney General’s report of the incident.

“They were brought here to carry out a sentence,” says the tour guide, “that sentence was not death.”

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments