Tags

Related Posts

Share This

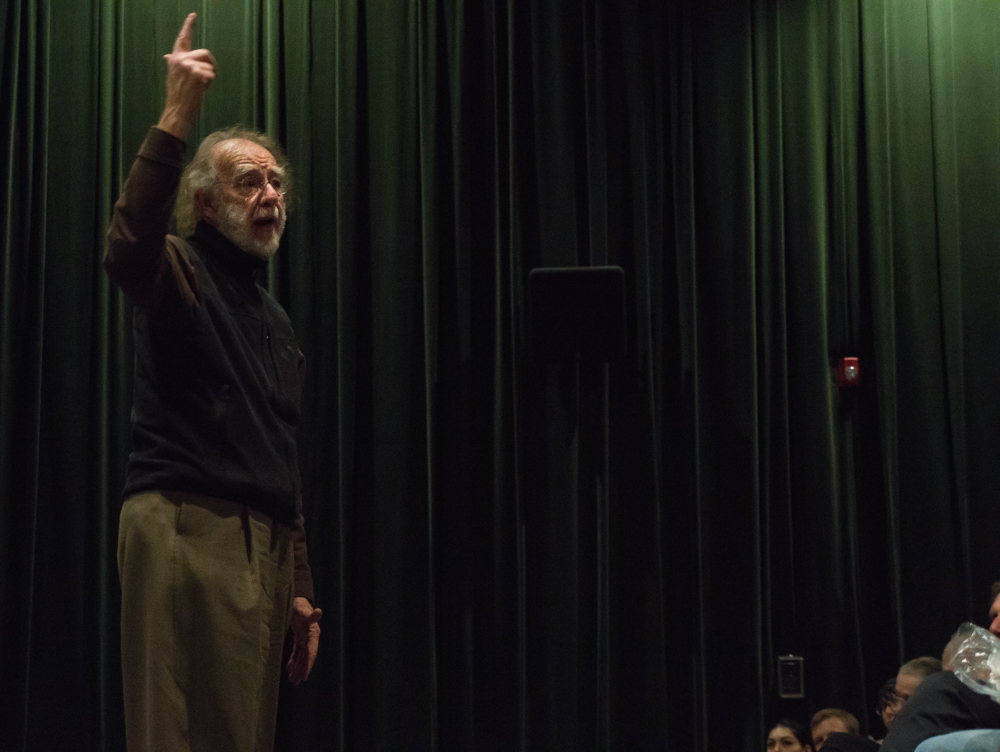

Q/A: Godfrey Reggio

“We live through the predicate of screens. They’re inescapable. They’ve become necessary to life.”

“We are the aliens on the planet and we’re eating it up for the sake of our pursuit of our technological happiness.”

—Godfrey Reggio (2014)

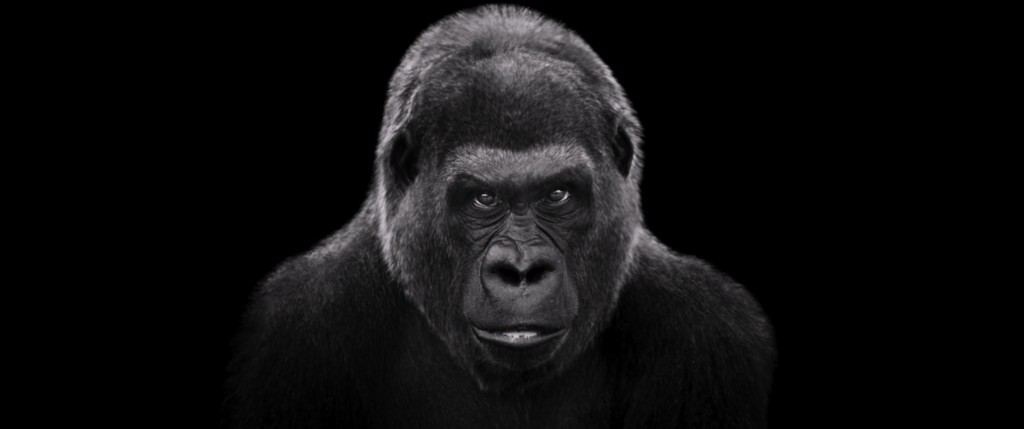

On Jan. 31, Director Godfrey Reggio, known for his film Koyaanisqatsi (1982), presented his newest artistic installment, Visitors, at the Screen. Considered a stunning portrait of modern life, Reggio’s film is a vivid black and white portrayal of slow-moving faces and places that are and yet are not of the ordinary world.

Movie-watchers sat flabbergasted by the heavenly white wings of Godfrey’s birds, the eerie depth of his city landscapes, and the haunting stares of the “watchers.” With cinematography by Steven Soderbergh and a majestic score by Philip Glass, Godfrey will again go down in cinema history with his latest endeavor. Below are Reggio’s responses during a Q & A with attendees.

Question: What inspired this?

Godfrey Reggio: I feel like I’m committed to an insane asylum. It’s not that I’m taking it out of my imagination. In a way (with my colleagues) I’m trying to give birth to something that is already present. After 2001, when I was finishing another film, Naqoyqatsi, for some reason the idea or the feeling for this film came to me and I spent seven years in prep for it. Being from New Orleans I was devastated by the storm. Had I got to film [on location] at the time that I wanted, it would have looked like the wreckage from a big storm. Having [New Orleans] stay there for five additional years made it appear like Pompeii or the ruins of modernity, which for me was much more articulated as a medium.

Q: What is the significance of faces?

GR: Our facial expression, our eye behavior, our gesture is as communicative as the language that we speak. That’s true of all cultures. When we go as Americans around the world they’re not hearing what we’re saying, they’re watching our faces, our behavior. Having said that, the human face (this is just a point of view for me and I feel for many people) is probably intrinsically the most interesting visage that we can see, because this is who we are. If you look at Caravaggio paintings very carefully with a microscope you will see in the eye little window panes, which is him giving away a point of view. What is inside of us appears on the visage of our face.

I learned as a young Christian brother then if you wanted to see that which was most familiar, that which is most ordinary, that which is most normal, if you want to see that which is present all the time, you must stare at it until it looks strange. We are pretty strange, from my point of view. I’m saying this from the point of view of a committed person, not with grace and gratuity, but like an insane asylum. We are moving so fast that we have no time to be still. The stiller one is the more possible one can be sensitive to that which is around them. Watch your animals, they’re very still. Why? They’re picking up the world around them. We’re not picking up the world around us. We live through the predicate of screens. Our life is based in screens. We use screens for the pursuit of our technological happiness. They’re inescapable, they’ve become necessary to life. So this film is really all about screens in some way.

Q: How did you prepare the actors for their scenes?

GR: In the cinemas I’m involved in, all the foreground of conventional cinema—plot, characterization, actor—is all riffed out in the foreground. In the business it’s called second unit production, which is where extras, buildings, traffic, etc. get you to the hamburger on the bun, as it were. When all of that is riffed out, the background becomes the foreground. All the people you saw were either volunteers or what’s called extras and the direction for them was to do nothing than what they ordinarily do. When I say that the people were non-self-conscious players I really mean that. Except two people in the film. The first six portraits…those are portraits from the inside out. They were asked, like you might be asked if you went to some city to get your portrait taken, ‘just sit still and we’re going to take your portrait.’ We didn’t tell them not to blink, we didn’t tell them not to think or to think about Katrina (because these were shot in Katrina and there’s some heavy thoughts). Those shots were done on a dolly so that it’s almost inhumanly slow so the modus operandi for the whole film is the moving still.

Every other shot of people that come after that are from the outside in. The predicate is the screen. The four children are watching television. The adolescence after that are gamers playing games and the group of people are in a sports bar that we created, a real bar for the final four basketball games. As soon as the TV comes on, it’s like a tractor beam. It’s like the young kids especially exhibit automaticity. A lot of eye behaviors…all the people drool a lot…we drool. You just watch your spouse or your partner when they’re watching television…mouths open…what I’m trying to say is that none of that was scripted. It was scripted by the context we put it in.

Q: Where is the swamp footage from?

GR: It’s the Atchafalaya Basin in Louisiana, it’s the largest river swamp in North America. It’s like one of the prime nurseries or suppose to be for the Gulf of Mexico. It’s a place of time and memory. If I may be so bold…we have a reptilian brain that has a memory beyond the literate memories that we have. It was an attempt not to show you that in beautiful National Geographic color but to show it to you in black and white and infrared, which could perhaps make more of an impression.

Q: How was the score prepared?

GR: It’s one medium motivating the other. I asked Philip Glass never to write note one until he’s been marinated in the image, in the ethos, in the emotive structure of the piece. We shoot the film first but he goes on location. Composers never go on location, composers now write music cues as long as several seconds and as short as several minutes, which means not very much. He’s writing in 87-minute 30-second symphony, then he comes to the studio and watches all the selects. In this film there are six discrete pieces of music. He decides where he wants to start. I respond to his first work on the piano and then it’s put onto samples, something we can edit with. It’s a collaborative form and one idea motivating the other.

Q: Where did you get the moon footage and why the moon?

GR: We had private spacecraft…no, the only footage we can get that existed in satellite is in what’s called 1080 [resolution]…it’s too low a resolution to use on a big screen. So what we did in the studio is collect maps of the moon that are accurate in terms of where the craters are, then through a 3D program we filled that out and created the moon.

As you know, from where we sit here about 63-65 miles straight up is this blue valence that we live in. Right on the other side of that it just happens to be all black. What I’m trying to say is the moon already has no atmosphere because organic life has disappeared from the moon as far as we know. This blue that we have comes from the decay of life itself, as I understand it. The moon is a sepulcher in a way. So the moon became a metaphor that we live in. As a filmmaker, I always want to know where the camera is. If you noticed, the only colored shot in this film is the blue planet and where is the camera? Off planet. From the point of view of this film, we are off planet. We’re living on the moon. We are the aliens on the planet and we’re eating it up for the sake of our pursuit of our technological happiness.

Watch Visitors at the Screen:

Sat, Feb. 8 6:15

Mon, Feb. 10 6:15

Wed, Feb. 12 6:15

Thur, Feb. 13

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments