Tags

Related Posts

Share This

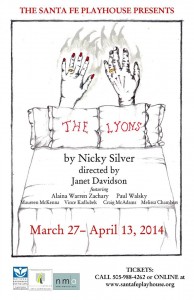

The Lyons

When a play opens on a man’s hospital deathbed, there isn’t a transparent opportunity for comedy readily available. In a different work, perhaps, the undeniably grim theme of death would have been spun into sugar by the power of love or given supposedly weighty significance by various characters’ profound reflections on human mortality. But The Lyons, Nicky Silver’s play centering on family dysfunction, which opened March 27 at the Santa Fe Playhouse and will continue to run through April 13, isn’t a play about people with delusions of idealistic outcomes.

When a play opens on a man’s hospital deathbed, there isn’t a transparent opportunity for comedy readily available. In a different work, perhaps, the undeniably grim theme of death would have been spun into sugar by the power of love or given supposedly weighty significance by various characters’ profound reflections on human mortality. But The Lyons, Nicky Silver’s play centering on family dysfunction, which opened March 27 at the Santa Fe Playhouse and will continue to run through April 13, isn’t a play about people with delusions of idealistic outcomes.

The Lyons is about people who hate one another, but for the most part they hate each other with style. The opening scene is nominally about the fact that Ben Lyons (played by a ruddy-faced, bellowing Paul Walsky, who manages to lend vulnerability to a despicably hateful character) is on his deathbed. He and Rita, his wife, are waiting for their two adult children to arrive, to say meaningful farewells. Rita is waiting for him to die so she can redecorate the living room, and chatters on about her plans with a cool alacrity that relates the reality of the situation immediately.

Alaina Warren Zachary plays Rita without shrinking away from the cold in her purposeful conversations, and the willful way she moves around the room, her orchestrating of hospital chairs to better fit her purposes, the straight backed power with which she imbues Rita Lyons, gives the play an active figure to gather itself around. While Ben serves as the apparent focal point at the play’s opening, he is largely an inactive, static figure, powerful only through the recollection of past misdoings visited upon his family.

Rita is the one who goes at the children with questions and insinuations the second they appear, and they respond accordingly, bounce off of her and one another in a tightly wound sequence that illustrates the level to which the Lyons family may be gathered together to bid their husband and father farewell, but will inevitably end up on the never-ending carousel of insults and manipulations borne out of neglect and selfishness.

Lisa (played by a nondescript Maureen McKenna), the daughter, is divorced with two kids, and still wants her ex-husband back with a sort of innocence that the rest of them undeniably lack. She clings to the need to call her AA sponsor when she’s frightened and a small hope of tenderness exists between her and her brother, the gay son hated by his father. Curtis (played by Vince Kadlubek, whose Curtis sidles around stage with a striking blend of rich-boy cockiness and simmering inner strangeness) and she don’t manage to hang on to it long, however, and descend into clever retorts and backhanded exchanges that, like Warren Zachary’s superficial unrepentant matriarch, draw more laughs than not.

The Lyons are bitter and cruel but they are also amusing, and the laughter reflects the discomfort inherent in being presented with a comedy that is in most places the kind of comedy that is very nearly tragic and very nearly not funny at all. While the script is in some places striking in terms of dramatic content, the success or failure of this performance of The Lyons arguably hinges on the performances of the four actors portraying the eponymous family members, and the verbal exchanges flung between the characters leave little room for actors to stumble. The lines are too sharp, too lightning-bolt short, and the timing of these exchanges is vital. A pause and Lisa’s reaction to her brother’s betrayal of faith is no longer a reaction, just a string of words that would have held meaning a half second earlier and fall flat, leaving the audience remembering that they are really just watching a bunch of damaged people expend themselves on hatred and manipulation.

The potential for action and reaction builds at the beginning of Act Two, where Silver’s script again lets the jab of question and answer rack up tension between Curtis and Brian, a real estate agent (played by a genuine, on point Craig McAdams, whose open, expressive physicality plays off Kadlubek’s lean, prowling Curtis first naturally and then explosively).

There are several solid moments in which the cast take the scene and manage to infuse personality into the production—where, for instance, Rita would not have dazzled in her final exit, or Curtis’ emotional isolation would not have been somehow suddenly very sad. These performances help carry the last act, which hits a high with Rita’s announcement and then leaves the last several minutes of the play lukewarm in places, struggling to remain as sharp in tone as before while simultaneously wrapping up the remaining two Lyons and their reactions. In the end, though, Silver’s Lyons find themselves in a place that offers a thing perhaps previously unattainable.

The play ends where it began, with a man in a hospital bed. But this is not a deathbed, and by the time Curtis asks the nurse what her name is in a tone of voice that suggests this is a real question, not an insinuating tactic of manipulation, the play has shifted. The destructive wreck of so-called family is abandoned for a moment, for this moment, and so the play ends too with a beginning, with a man in a hospital bed waiting for a change that is inescapable.

The Lyons

Through April 13

Thursdays, Fridays & Saturdays at 7:30 p.m. & Sundays at 4 p.m.

Santa Fe Playhouse

142 East DeVargas Street

Call 988-4262 for tickets or purchase online.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments