Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Q/A: Emily Kendal Frey

Affection is a dumb dog.

Whoever said that

didn’t own

me,

was not

my master

—Emily Kendal Frey

Part of Muse Times Two at Collected Works Bookstore, poet Emily Kendal Frey along with Kim Parko read for the Santa Fe audience and students from SFUAD’s Creative Writing Department on Nov. 16.

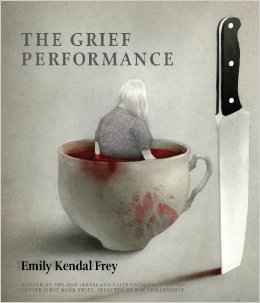

Poet and CWD faculty member Dana Levin introduced Frey and her book The Grief Performance saying, “I was deeply suspicious of its maneuvers, its brevity, but I couldn’t quit thinking about it.” Levin explained that as a member of the Poetry Society of America and final judge for PSA’s Norma Farber First Book Award she decided that “if you couldn’t quit thinking about a book, it should probably win the prize.” Consequently, Levin awarded Frey the 2012 prize for The Grief Performance, which is now one of two of Frey’s published collections.

“Wily, witty and weird,” Levin continued in her description of Frey’s work Sunday night, “often haunting, sometimes heartbreaking, [Frey’s] poems dive deep for all their individual brevity. They prove Hemingway’s iceberg theorem that a certain ‘dignity of movement’ comes with confident omission. We never get much autobiographical detail from these poems, nor are their assertions and arguments exhaustively presented; in this they stay true to the silences and gaps that confront us always in our quests for certainty and knowing. The closest we can get to knowing, Frey suggests, is to be like the lovers in ‘Love Letter,’ who each hold ‘a particular weight, carrying something” that they can feel moving in their hands.'”

Reading from The Grief Performance as well as her new collection Sorrow Arrow, the ensuing questions posed to Frey interrogated her style, her themes and her general outlook on the art of poetry.

Jackalope Magazine: Your work seems very dense and deep. Was that a conscious decision or did it come naturally in The Grief Performance?

Emily Kendal Frey: I think your first book is the product of your whole life up until then. You’ve had a lot of time to marinate on your topic, your manuscript has usually been rejected so many times that you’ve worked it, worked it, worked it. I think that I have been working on it for so long and getting at the essence of what I was trying to say…for me, [The Grief Performance] still makes me uncomfortable. I think that when you’re trying to do your best or make something good it’s usually not in the ways you anticipated. You’re like ‘my task here is to leave that alone even though it feels awkward and weird.’ I still feel weird about it.

JM: What does the poem form afford you?

EKF: Part of the revision and part of the working on it for 30 years, or whatever, there’s moments where you’re like ‘stop bullshitting.’ What is it you’re trying to say? I got to write some grief poems. I felt like that was the form. I think it afforded me uncomfortable bravery. That book doesn’t feel warm and fuzzy to me.

JM: How did your favorite teacher inform your work?

EKF: My favorite teacher was Bill Knot. His teaching style is really cool. We had to take a [poetry] forms workshop, so you worked on a sonnet for two months. First you had to bring in the first four lines of your sonnet and you would have to write your first four lines on the board. The whole class would sit with their rhyming dictionaries and help you adjust the first four lines. To me, that just crafted my whole ego and sense of self. Wide open. Just up there on the board. You hated it, you hated everybody, but then you’re like ‘oh, this poem doesn’t really belong to me, it’s just language that I’m participating in.’ He made my poetry about the world.

JM: Once you know you’re not your poem, how does that change the way you write and revise?

EKF: Once you see that your poem is external to you, I think you can be less narcissistic and self involved. I think every writer has a certain amount of that that needs to come out. It’s toxic sludge, but the faster you can get that out the faster you can get to writing poems that are about real things that involve other people in the world. At first, you’re just writing from your own very limited perspective, which makes sense because that’s all you’ve experienced until that point. The sooner you can let the world in, the more interesting it will be to you and everybody else. I think we think too that if we let the world into our poems, ‘I’ll be bored or overwhelmed or it won’t be my poem anymore.’ That’s not true, your poem is really boring if it’s only about you. And it will be boring to you within 10 minutes or 10 days. You can speak on behalf of the world.

JM: What is the essence of The Grief Performance?

EKF: Loss. Grief. What does that mean that I’m still alive and happy and thriving even though I’m deeply upset? Am I allowed to have both things? Can I toggle back and forth? Can I get away with that? Can I feel this giant overwhelming love attack for the world even while I’m very dismayed and disappointed and everyone is dying around me. I think art is trying to make a space where both those things can be true. We feel more integrated as human beings through art. I just want to participate. I feel like when I don’t like a poem, I think it’s trying to ask me to make a choice, make things one way, and I don’t like that. Or at least you want to feel like the writer is aware that there are choices to be made. It’s not just, ‘here it is!’ That’s not accurate, that’s not how life is. I think also that in our culture there’s not a lot of space for grief or sadness. It’s very confusing to people when you’re confronting that with joy, or with reverence, or spirituality. I don’t blame people, it’s just they don’t have the language for it, they don’t have the context, they don’t live in a culture that has a lot of ritual. That’s not our culture. It feels like poetry is maybe a place where we’re trying to do some of that.

JM: What sort of tips would you give a writer?

EKF: This is one of my tricks when you feel stuck. You describe an image, have a feeling, describe an image, have a feeling. Not that that’s ultimately a good poem, but you just pulse between what is already happening. Usually you get stuck between one thing or the other; thinking or feeling, observing or having an idea. Not just observe, not just feel, have both. Sometimes that pulse is still boring…but my other trick is called “third thing.” I’ll have a thought, then I’ll have a second thought, then I’ll be like ‘ok, what’s the next thought?’ I never allow myself to write the second thoughts, just the first and third thoughts. An example: ‘I’m sad’ ok what’s the image? Hairdryer. So I have sad, hairdryer. Then I’m like ‘nope not hairdryer, what’s the third thing?’ Antelope. I need to push if I‘m more interested in surprising myself. Sometimes even if you write down the second thought, you take it out, because it’s just a landing place. I want to think beyond my regular one, two [thoughts]. If you can have patience and see what’s next, that’s often more interesting and people respond to it. You’re allowing yourself to move beyond yourself.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments