Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Verve Photography Exhibit

Norman Mauskopf’s, New York, New York, 1985 from the series American Triptychs. Photo by Ashley Costello.

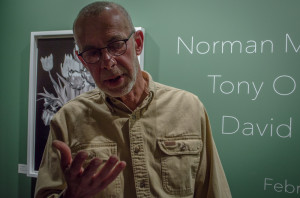

“In the world of academic photography, the word ‘triptych’ refers to putting three different pictures together to make one composition,” says Norman Mauskopf, whose American Triptychs debuted at Verve Gallery of Photography on the evening of Feb. 6. He twists the brim of a sun hat in one hand as he speaks. Norman Mauskopf’s triptychs make up one third of the gallery alongside the calotypes of former SFUAD Photography Director David Scheinbaum. In a smaller room, off to the side, are a series of Syrian refugee portraits taken by photographer and current SFUAD Photography Director Tony O’Brien.

Santa Fe-based Norman Mauskopf is approached several times as he explains the history of triptychs and the influences on his work. The gallery has only been open for half an hour, but more than 100 guests have already walked through the door. A chocolate lab, bearing an animal assistance vest, sniffs at a woman’s snakeskin boots and wags its tail. Children race between the adults, oblivious to decorum.

“I’m only stopping by for a moment,” says one woman. “I have several other gallery openings to attend tonight.”

A man in a bolo tie with a skull-shaped clasp walks past the free-standing gallery wall. The negative image of a vase of flowers, photographed by David Scheinbaum, hangs on the wall beside the painted titles of the exhibits: “Norman Mauskopf American Triptychs, Tony O’Brien Sketches from Syria, David Scheinbaum Kalós.”

“We like to do a local show at the beginning of the year,” says gallery Director Jennifer Schlesinger. “This exhibit has three artists with all new work, created within the last couple of years.” Schlesinger is a photographer herself, having graduated from the College of Santa Fe and studied with two of the three men whose work is on display.

Norman Mauskopf

Norman Mauskopf discussing his series, American Triptychs during the opening reception at Verve Gallery. Photo by Ashley Costello.

A series of oversized teepees span across three photographs in Norman Mauskopf’s triptych, “Holbrook, Arizona 1991.” Upon closer inspection, one can make out doors on the front of the teepees and the letters of a sign obscured by a wooden fence. The photographer’s shadow paints the surface of the fence, a negative image of Mauskopf himself. “That’s actually a motel,” says local photographer Ward Russell who attends the opening. “You can stay in those wigwams.”

They are designed to look like teepees, but the actual name of the motel is Wigwam Village Motel #6. Russell points to another piece, “Cabazon, California 1984.” A concrete Apatosaurus named Dinny the Dinosaur towers in the background, while an eighteen wheeler makes up the foreground. Russell recognizes both locations. He has his own gallery in Santa Fe and his website bio gives a list of his mentors, among them David Scheinbaum and Norman Mauskopf.

“Art is inspired by old art,” says Mauskopf. “Everyone borrows from someone else.” American Triptychs, a series of images shot between 1981 and 1991, was heavily inspired by the work of Walker Evans. A documentary photographer, Evans was known for his images of everyday, American life, a style known as vernacular.

While on the road, working on other projects, Mauskopf occasionally took a break and went out on his own to photograph some of the “quirkier, interesting spaces” of America. Not having the money to spend on a Widelux panoramic, he used the same Hasselblad camera he was using for portrait work. “With a wide angle lens, the foreground gets exaggerated and the middle ground and background get pushed away,” says Mauskopf. With the lens on his Hasselblad, he was able to get a “square, more natural perspective.”

To reproduce the landscapes, Mauskopf would take a photo, turn the camera on the tripod, take another photo, turn the camera again, and take his final photo. “There was no Photoshop back then,” he says. “You couldn’t stitch them together.” This resulted in what Mauskopf calls “kinks” in some of the finished compositions, most notably in his images of the Brooklyn Bridge and a storefront in El Paso, Texas. He feels this contributes to the already odd subject matter of the photographs. “My main interest was in capturing the quirky nature of the subject or space. The lens gave the true perspective in each frame, but it looks different when put together.”

Except for the occasional New Year’s card, the images had not been printed before this exhibit. When Verve Director Jennifer Schlesinger asked him if he had anything new to display, he said, “I’ve got some stuff from 30 years ago that nobody’s ever seen.” Out of 170 compositions, Mauskopf has chosen only 10 to display. “The success rate of photography is mostly failure. When the images are divided, they’re not great. But when put together, the composition has some integrity.”

David Scheinbaum

“Feb. 8 will mark the 174th anniversary of calotype photography,” says David Scheinbaum, whose exhibit, Kalós, is made up entirely of calotypes. The word, “calotype” comes from the Greek roots, “Kalós,” meaning beautiful, and “type” meaning picture. The process was invented by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1841 and involves loading film into the holder of a view camera and taking one picture at a time. “The average exposure takes four to four and a half minutes,” says Scheinbaum.

Anyone who has ever taken their film to be developed at a local drug store will recognize the odd coloring of Scheinbaum’s pieces: white outlines on a blanket of darkness. Scheinbaum used paper in his camera rather than traditional film. When it came time to print the images, he realized that he liked the negatives better. “I could print the positives,” he says, “but they would lose a generation of sharpness. The negatives are more beautiful.”

Half of his subject matter consists of antique photography equipment: Kodak film cans, an Ansco Shur Shot, a Brownie 8mm movie camera. He uses the oldest method of photography to document the history of the profession. Why return to calotypes? “I’ve done some work with digital,” he says, “but technology just gets more complex and more complicated. It gets to be a burden on my art. I spent so much time learning how to develop film properly. With technology, I started losing my grasp. This work is the beginning of an attempt to simplify.”

Film equipment is not Scheinbaum’s only focus. “Homage to AWI,” “Homage to AWII” and “Ajax” are all photos of common household items, and as the names suggest, are an homage to Andy Warhol. Several of Scheinbaum’s original calotype negatives are on display, depicting statues of religious icons, including: “Happy Buddha,” “Ganesha,” and “Santa Lucia.”

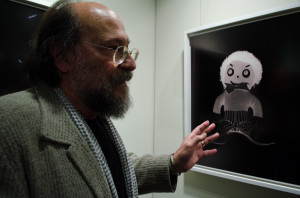

Standing apart from the other prints is what looks like a manic clown, glaring down at gallery goers. With a plastic coffee mug dangling from his hand, Scheinbaum explains that this photo, simply titled, “Doll,” depicts an item of racist memorabilia. A blackface doll, now presented in reverse luminance, is made into a whiteface doll. In beginning a new body of work, Scheinbaum has taken on photographing “a whole generation of objectionable objects. If you go on Ebay, there are some really terrible things out there. I’m glad no one looks at the packages I’m getting. My intention is to create a whole body of work making negatives of negative things.”

Tony O’Brien with his new works Sketches from Syria on exhibit until Apr.18. Photo by Ashley Costello.

Tony O’Brien

The day after the opening, mineral water is served on the porch of Verve Gallery. A meter maid writes a ticket for a Mini Cooper out front. A light breeze blows through the door and a square of sunlight paints the wall where Norman Mauskopf’s triptychs hang. Visitors trickle in and take their seats for a gallery talk. Each of the artists speaks as images of their work scroll on a Sony flat screen behind them.

Tony O’Brien is the last to speak on his work, Sketches from Syria. Wearing his trademark vest and a pink button-down shirt, tall and lanky O’Brien deadpans, “This is probably more frightening than going to Jordan.” In the summer of 2013, O’Brien was asked to travel to Jordan to photograph Syrian refugees. A longtime war photographer, O’Brien says he is “not interested in conflicts anymore. I prefer to document the plight of humanity. As photographers we take, and it’s important to give back.”

O’Brien considers himself self-taught. He didn’t look at the work of other photographers for many years because he felt insecure. He points to one influence, a photographer named James Nachtwey, a man who has “devoted his entire career to documenting man’s inhumanity to man.”

Norman Mauskopf pipes up from the corner, “There’s a documentary about him on Netflix right now called War Photographer.” O’Brien nods in affirmation. Anyone choosing to go looking for Nachtwey’s work should be advised: his images are extremely graphic.

Though O’Brien was in Jordan for two weeks, he only shot for seven or eight days. At first he simply hung out and watched. The Zaatari refugee camp was a three-hour drive from where he stayed in the city of Amman. “I would get there at 11 a.m. in the desert, and I would leave at 3:30, just when it was getting to be the best part of the day.” Sometimes he was accompanied by an interpreter, but he preferred to go off on his own. “I’m not much of a techie,” he says. “I gave up on big cameras a number of years ago and switched to smaller ones. With big cameras, people can see you a block away.”

“You’re a big target,” says an audience member.

“Yeah, but I can turn sideways,” O’Brien replies and demonstrates.

Chelsea Garcia, a student of Tony O’Brien at Santa Fe University of Art and Design, views his new works, Sketches from Syria. Photo by Ashley Costello.

O’Brien documented stories from the people he met in the camp. He asked the refugees to show him their most important possessions. Almost all of them responded by pointing to their children. A woman named Razan presented O’Brien with a miniature Koran. One of the most exquisite photos in the exhibit, the open book with its ornate, Arabic lettering, is settled in the palms of Razan’s hands.

Most of O’Brien’s photographs are pictures of children. A woman in a tiger-print hijab holds her daughter in her arms while the child clings to a bag of instant noodles. In front of a UN Refugee tent, a young girl, garbed in red, carries long, leaved branches. An extreme close-up of a child, her face speckled with drops of water, captures eyes so wide and pure, they are almost pleading.

“The truth is they are traumatized,” says O’Brien. “They have nightmares.” Outside Zaatari, while stuck in traffic, a boy, no more than six years old, leaned his arm on O’Brien’s window. “That was one of those situations where I took the picture and then it was like, now what? Do I give him money? What do you do?” O’Brien says they are like children anywhere else in the world. “I have photographed a lot of adults. Not to be cynical, but children are more honest.”

There are no titles listed next to O’Brien’s photographs. When asked to show his work from Jordan, he didn’t think it could hold up as an exhibit. “That’s why it’s called ‘Sketches.’ This is just the beginning.” O’Brien hopes to bring some SFUAD students along next time as part of an internship. “I want to spend more time there and make a larger body of work.”

The exhibit of all three artists will be on display from Feb. 6 through April 18.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments