Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Common Humanity

Mike Sager’s resume reads less like a timeline and more like a greatest hits reel, with all his stories as steeped in history as they are. Having worked early in his career at the Washington Post under Bob Woodward, he went on to work at magazines such as Rolling Stone, GQ, and Esquire, where he is currently a Writer-at-Large. His stories range from subjects as varied as celebrities to murderers, Paris Hilton to Warren Durso, whose greatest claim to fame is his apparent ugliness. Yet whether he is writing about famous porn star John Holmes or disgraced former journalist Janet Cooke, it is his empathy that stands out for the reader. Through Sager’s work, dignity is returned to his subjects, their lives and stories reclaimed from a public eye that perhaps sees public figures as entertainment first and human beings second. During a whirlwind two days in Santa Fe, Sager granted interviews, readings, and visited SFUAD classes as the Creative Writing and Literature department’s Fall 2016 visiting writer. An interview with Jackalope Magazine brings him to a warm outdoor patio, a half-finished cup of coffee resting on the table as he contemplates a reporter’s role in portraying his subject.

Writer-at-Large for Esquire Magazine Mike Sager reading excerpts from his articles for the Creative Writing and Literature majors at Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Photo by Yoana Medrano.

Sager emphasizes the importance of ministering to his subjects rather than accusing them. In the introduction to his 2012 book The Someone You’re Not, this is referred to as suspending disbelief long enough to hear what someone is saying and arrive at a new understanding. He uses the children who shot nine Buddhist monks as an example; in the moment one of them confesses to the killing, “you have to just say, ‘I’m here with you, I’m listening.’” To try and render a full person, it’s important to “[put] your fears aside long enough to listen.” At the end of an interview, some sense of commonality is found, something that unites both interviewer and interviewee. His goal is to have “a little piece of that person’s truth there on the page.” Sometimes to get to that truth, an “ethical understanding” must first be reached between both parties. With a subject who may be or may not be linked to questionable activities, Sager focuses on what he needs for his story, not addressing it as per their silent agreement. After a lively reading Oct. 11, punctuated by excitable hands and karaoke’d Kendrick Lamar lyrics, Sager affirms the need to suspend disbelief and “tell the truth kindly” when questioned by curious students.

Part of rendering someone else’s truth is ensuring their comfort throughout the interview process. For this, Sager has a system to keep the focus where it should be—on his interviewee. His preference is to spend multiple days with a person, asking as few questions as possible to allow them to speak for themselves. After a moment’s pause, Sager chuckles as he lights upon the perfect metaphor for his process. “I just want to be like a little kid in the workshop following his daddy around.” Questions tend to be more to clarify what a person has said rather than probe for specific information. However, in a situation where time is of the essence, Sager begins the interview by getting someone’s biography. “Starting out with a bit of a bio is a way of putting people at ease,” he explains after a sip of coffee, which is slowly going cold in the shadow of the patio umbrella. “It’s like a good date. [Being] a good listener… that’s the secret to winning friends and influencing people.”

Overwhelmingly, Sager’s stories are dominated by the third person, only occasionally allowing his own voice to break into the piece. In response to a question about this at another Q&A, Sager declares that he is firmly anti-first person, though readers seem to respond well when he does employ it. His policy is to “save it for a story that needs it,” where his presence will improve the story at hand. As for knowing when specifically to make that decision, that comes down to experience. “[Being] a writer, an artist, [is] like…driving down the highway…in four-wheel drive, and you turn right and crash through the barrier.” In other words, writers learn by doing. Sager first references the idea of faking it until you make it, then corrects himself. “It’s more than faking it. You [try] it till you make it.”

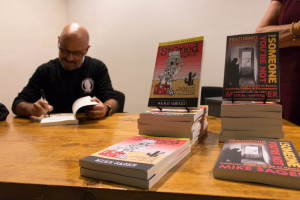

Writer-at-Large for Esquire Magazine Mike Sager signing his books after reading excerpts from his articles for the Creative Writing and Literature majors at Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Photo by Yoana Medrano.

As Sager’s time in Santa Fe comes to a close, he has some final advice for other writers. Reminiscing about his experience as a freelance writer and trying to get established, he adds, “Part of being a writer is being an entrepreneur.” As a writer, one must be the factory and the creator and marketer and the product all at once. It’s all about building a brand for yourself. In modern journalism, there is a lot of opportunity to establish oneself before approaching an outfit for a job. The more multimedia skills a writer has today, the more their own brand is strengthened. “We enable ourselves to be different.” Another point Sager emphasizes is the importance of internships, which give students skills in the workforce that will stand out to potential employers. For writers breaking into journalism today, his tone is hopeful. Writers have many opportunities out there to pursue writing in a “semi-independent” way, something that was less available to Sager when he got his start in journalism. As the final Q&A wraps up, he shakes the hands of those in attendance, collects business cards, and sweeps out of the room amid a smattering of grateful applause and chatter from students who now have the benefit of all he’s shared over the past two days, knowledge they can carry forward into their careers.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks