Tags

Related Posts

Share This

On the High Road to Taos

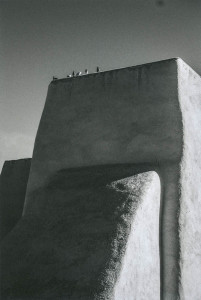

A black and white photograph of the pigeons who live on the San Francisco de Asis Mission Church in Taos, NM. Photo by Miguel Martinez.

The archway leading into the El Santurario de Chimayo grounds is flanked by a long chain link fence on the left side. Colorful handmade crosses, rosaries, ribbons, jewelry, flowers and other miscellaneous items visitors have left behind decorate the fence, making it look like a rainbow full of sunny gaps. Toward the center of the fence, a pair of ratty, white shoes hang with thick locks of hair sticking out of one of the sneakers.

After squeezing nine students into a small shuttle bus, Photography Department Chairman Anthony O’Brien and Technical Faculty member Chris Nail took the high road up to Taos on Nov. 12, 2016 on another trip into northern New Mexico to take photographs of churches and the New Mexican landscape.

“We’re gunna have to do headcounts so we don’t forget anyone,” Nail said to O’Brien as the students flocked around the table in the Marion Center at 9 a.m., filling out field trip safety forms.

About 45 minutes out, we arrived at Chimayo, an old Hispanic village in northern New Mexico. The town itself was nothing more than a few small houses no more than two or three miles long sitting along the side of the road. But the El Santuario de Chimayo, a Roman Catholic Church known for its healing dirt, is the town’s main attraction. Every Good Friday, people from all over New Mexico make a pilgrimage—sometimes on foot—to visit the chapel and take some of the healing soil so their ailments can be treated.

In the courtyard, seven stone crosses stood facing the parking lot. They are also decorated with the same colorful idols scattered along the fence. In fact, every statue in the chapel’s courtyard is decorated with at least one tiny cluster of flowers, crosses and rosaries. In the corner of the courtyard, one statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe sits in the crook of two stone walls. She is surrounded by various chalk and charcoal names and prayers that have been written on the stones at her feet and around her sides.

Bundles of dried chilies, some of them glistening with lacquer in the mid-morning sun, hang outside the front door of a shop nestled deeper inside the courtyard. A few feet away from the shop, there is a slushie-shaped sign featuring a blue and white dog standing on its hind legs, smiling and holding a slushie in its paws. It reads, “Slushie Puppie!” There is another sign next to the “Slushie Puppie” sign, this one a simple white rectangle with an arrow pointing to the left, reading, “Visit El Santuario Gift Shop for candles, containers for Holy Dirt and other religious needs. 150 yards ahead and to your left.”

The historic El Santuario de Chimayó in Chimayo, NM. Photo by Chris Dorantes

At 11 a.m., we piled back into the shuttle and pulled out of the chapel driveway, passing by a large, glittering cemetery on our way out.

“Did anyone get a change to take some photos of that?” O’Brien asked.

The shuttle fell silent.

“Shame,” he said.

“Hey, did anyone ever play that Mojo game where you hold your breath when passing by a cemetery?” Heather Suarez, freshman photography major, asked.

“That makes me think of Mojo Jojo, from the Powerpuff Girls,” Miguel Martinez, who sat next to her, said with a laugh.

Several miles outside Chimayo, we stopped along the side of the road to take pictures of a tiny, roadside town and the landscape surrounding it. The houses are small and dilapidated, with rusted metal roofs and crumbling wooden porches. They stood behind a rickety, wooden fence with disheveled planks. Outside the town, a small, broken down shack leaned against the edge of a cliff, threatening to topple over at the slightest puff of wind.

I snapped a picture of Willow Howell taking a photograph of a water tower covered in graffiti behind a faded Route 76 sign.

An abandoned storefront in Las Trampas, NM. Photo by Chris Dorantes.

Back in the shuttle, we talked about the election. We talked about Pence and the conversion camps he wants to build with taxpayer dollars, and how Donald Trump doesn’t know what he’s doing. We talked about Hillary Clinton winning the popular vote, and about moving to Mexico or Canada. We talked about electing Kanye into office—because if Trump can win the presidency, Kanye should have no trouble winning it also. Even with the New Mexican landscape rolling passed us, fear permeates the air.

Our second stop of the day is the Church of San José de la Gracia, in Las Trampas, a Spanish-American community established in 1751.

“OK, everyone needs to come up with two prints from the pictures you’ve taken during today’s shoot,” O’Brien instructed as we all climbed out of the shuttle. “So, choose your two favorite pictures and we’ll hang them up on the wall in Marion.”

We scattered around the churchyard to take photographs, as the church is closed for the day. Behind the church is a small cemetery surrounded by a chain link fence. A small, neatly cut grey headstone sits behind a cross with white and pink lilies covering the surface. A barrel and a large black trash bag are heaped together in the corner of the cemetery. A few feet away from the cemetery, a plastic child’s swing hangs from a rusted metal stand. Across from the swing, a clothesline with clothespins still on it is tied to an identical metal stand.

A few feet away from the chapel behind a rickety wooden gate, O’Brien, Eduardo Rocha and Martinez stood outside a convenience store that has plywood tacked onto the front of it with a tin roof.

I ducked down behind the gate and peeked at them through the gaps in the wood as O’Brien instructed them to look through one of the small

An old roof top in the historic district of Las Trampas, NM. Photo by Chris Dorantes

rectangular windows. “See how the light reflects off the glass, and the colors on the building? It might be something, it might be nothing, but these are some of the things you need to keep in mind when you’re looking to make photographs like this.”

At that point, it was 12:30 p.m., and everyone was hungry. So, we piled back into the shuttle to find a place to eat lunch. We talked about the election again.

We stopped for lunch at a rest area somewhere between Las Trampas and Taos across the street from a winding dirt road disappearing around a forest of trees. We scattered among the trees to eat lunch after petting an adorable German Shepherd puppy out on her first hunt. Chris Dorantes and Howell sat away from the other students, who had formed a little group under the trees. O’Brien and Nail ate in the shuttle. The porta-potties had no toilet paper.

We got back in the shuttle.

“Is everyone here?” O’Brien asked as he climbed into the driver’s seat.

“Yes,” everyone murmured.

We started backing out of the rest stop.

“Wait! What about Miguel?” Suarez cried, sitting up straight in her seat.

“Miguel?” O’Brien stopped the van and Martinez walked up to the shuttle, grinning.

“I guess we weren’t all here,” Nail said.

“Is everyone really here?” O’Brien asked.

We count heads just to make sure, and then talk about the election again.

The San Francisco de Asis Mission Church in Taos is the center of a tiny plaza. Worn down houses with off-white lace curtains and dried chili wreaths sat beside equally shabby shops—most of which were closed for the day. A frisky grey and white tabby cat scampered across the parking lot and ducked under a car.

“Most of the photographs that have been taken of the church have been from the back because of its angles and shadows,” O’Brien told us.

Directly across from the church is a derelict shack with boarded up windows and doors. Inside, rotten planks of wood lay on the ground and sheets of tin seep into the building from holes in the ceiling. Broken glass and jagged clumps of adobe litter the windowsill. Several yards away from the shack, a screen door with a blue border hangs a few centimeters open. A cement pathway leading into someone’s backyard can be seen through the screen.

Rio Grande Gorge bridge in Taos, NM. Photo by Chris Dorantes

A shallow, dry well surrounded by the scattered remains of brittle animal bones and iridescent black and blue feathers hides behind the church.

We sat in the churchyard, resting our feet, checking our phones, and chatting. I sat on the ground across from a headstone, the words etched into it much too faded to read, and ran my fingers along the steep cracks in the stones on the ground. Behind me, a statue of St. Francis stands perched on a round stood made up of large stones.

After taking a group photo in front of the San Francisco de Asis, we headed back to Santa Fe along the Rio Grande Gorge. The canyon beneath the bridge is shrouded in late afternoon shadows, but the river at the bottom of the gorge can still be seen clearly, gleaming like a trickle of silver mercury under the clouds.

Crisis hotline call boxes lined the bridge’s long stretch. The bridge has been the site of several suicides over the years—someone will drive down to the gorge, climb onto the bridge’s rail and jump. A large red button sits above a speaker with the instructions, “Push to call” next to it. Above the button, are the words, “There is hope. Make the call.” In the distance, behind the crisis boxes, the snow tipped mountains stretch into a blanket of grey clouds towards an endless blue sky.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments