Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Q&A With Danielle Evans

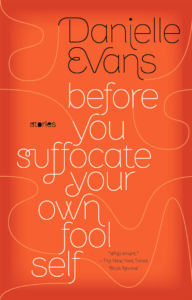

Danielle Evans’ first short story collection, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, was dubbed “whip smart” by The New York Times. (Photo credit Nina Subin)

Santa Fe University of Art and Design’s Creative Writing and Literature Department hosts visiting writers each semester for readings, book signings and classroom visits. This spring SFUAD is welcoming Danielle Evans, author of Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, which won the 2011 PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize. Evans’ stories offer a realistic look at youth, race, class and relationships in America. Her writing has been published in The Paris Review and A Public Space, and the National Book Foundation named her one of 2011’s “5 Under 35” in fiction. Jackalope Magazine talks with Evans about her writing process and creative inspiration in anticipation for her campus visit next week.

Jackalope Magazine: Your writing frequently explores identity and relationships in ways that will continue to be relevant for years to come, especially for readers who crave this type of representation in literature. Are there any themes you’d like to see more of when you read books?

Danielle Evans: I think on some level the theme of all literature is the struggle with some kind of cognitive dissonance: who we think we are versus who we turn out to be in the world, what we thought we wanted versus what actually brings us joy, how complex the world can be even when our desires within it seem simple. So, I am interested, always, in books that wrestle with that space of ambiguity, in work that thinks about the way we lie to or perform for other people and the points at which those lies or performances become the actual people we are. I am interested in books that find new versions of those questions, whether the sensation of the work being new comes from the writer’s voice, or particular insight into characters whose lives haven’t been given much space in fiction, or talent for creating narrative tension that puts pressure on those questions and asks us to reflect our answers back out into the world.

Are there specific pieces of art in mediums other than literature that have inspired your work?

I don’t know that there’s a particular work of art that I’ve responded to directly—ekphrasis has a grand tradition in poetry, but perhaps less so in fiction. But I do think a lot about music and visual art. I’m always fascinated to talk to artists who work in those mediums, because I think of the work of writing as being so much about revision, about getting the thing on the page so you can see what’s there and make it into the real thing, and in some cases other kinds of creative endeavors require a different perspective from the outset, a different sensibility about what you’re committing to with your initial vision and what can be changed and how you find your way into that change.

So, I like going to museums and concerts and taking in new work and trying to piece out the process behind it. One of the characters in my novel is a singer and actress whose voice work is mostly covers, so it’s been interesting, in writing her, to think about the way she hears songs, and the space in which she finds in them a way to make them her own or communicate something about her life and the world. Another is a visual artist whose paintings are all direct responses to white artists’ famous renderings of women of color, so I’ve thought a lot about what it means to her to remake something with the intention of taunt or critique, when her language is image and not words.

I also think a lot about television and film as narrative forms. They have, certainly, storytelling capacities that fiction doesn’t, so I think a lot about the narrative spaces that still belong to fiction. I like TV, and movies, but I find less that any particular show or movie is a model and more that what they teach about writing is to find the spaces where interiority matters most, where the possibilities for fiction to illuminate the tension between the public self and the private self are greatest, because that’s the storytelling space that feels most distinctly ours.

Your talent for creating parallels between characters within your stories is astounding. Is this a tool you’ve always liked using? And why do you think it’s effective?

Thank you. I think this is often a phenomenon that emerges in revision—you let a first draft follow characters as they wander, and then you figure out where their plot or thematic intersections and overlaps are, and pull those into focus in later drafts. Partly this is a way of letting the story have its own narrative life without spinning too far from the center that’s holding it together. But foils are also fundamentally about character and motivation. Where do we see ourselves in other people? Where do we see ourselves reflected when maybe we shouldn’t, or not see ourselves when we should?

Danielle Evans’ debut collection of fiction from Riverhead Books.

Why do you enjoy writing fiction?

Anyone who is in the middle of revising a book and answers this question without hesitation is lying to you. My first response was one of those laughs that can’t tell if it wants to be sobbing. Writing is difficult and I think should feel difficult, which is not to say joyless. The joy for me comes from those moments of revelation, not unlike the moments I have as a reader—the places where the heart of the tension, or the real underlying question, shows itself in some way that I recognize. I rarely write my way into answers but I often write my way into the right question.

What is your writing process like both physically and mentally?

It’s usually to get to the end of a first draft as quickly as possible and then stand back for a bit and assess what’s there before deciding on a concrete direction for revision. Of course ‘as quickly as possible’ can be a matter of days or a matter of years—some stories take longer to present a course to follow. I don’t have a time of day I write or a particular routine, though I try, these days to work in coffee shops because it means declaring writing days as writing days, and also being dressed and out of the house and not inside alone turning feral.

Do you ever run into any speed bumps with your writing? How do you overcome them?

The speed bumps are the process. I think that’s the important part to remember—if we’re not working with the possibility of failure, our work probably isn’t taking enough risks. The harder part is knowing when a block or disruption is telling you to rethink the project and when it’s telling you you’ve come to the hard part and need to push through. There isn’t a science for knowing which is which, though usually when you’re avoiding something because you’ve come to the difficult part, on some level you’re aware of it.

What’s the worst piece of advice you’ve ever received as a writer?

It’s hard to think of a piece of advice that would be uniformly terrible for everyone. I think the advice I resist most is advice that presumes there’s one way that works for all writers, such that if you’re not doing something a particular way you’re doing it wrong. I’m never personally going to be the write-for-two-hours-every-morning kind of writer, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a good process for some people.

So, most of what I’d characterize as the worst advice is people being didactic about process. I do remember once, very early on, getting workshop feedback from a classmate who was concerned by how conscious some of my characters were of racism or the possibility of discrimination. He wanted me to rethink the story in such a way that the structural racism would be subtly revealed to the reader but was not explicitly noted by the characters in the story. And I’m sure that felt true to him and his experience of gradually noticing such things, as a person who considered himself to be an enlightened white person, but it would not have been true to the experience of two black girls in an unofficially segregated school system. It would not have been realistic that racism would not occur to them as a possibility. Advice that didn’t consider that they, or I, might have a different experience of the world in which direct conversation about race and racism was a regular occurrence wasn’t helpful. So, sometimes you get that kind of advice and just have to know the world of your story well enough to ignore it. But honestly, the very worst advice is probably always ‘it’s perfect don’t change it,’ and there is probably a time I heard that and listened and am not even aware yet how much of a mistake I made.

If writers were to have one responsibility as artists, what would you say it is?

Responsibility always feels like such a loaded word. Art is unruly and suspicious of too much regulation and authority and I would never prescribe a singular mode of work or purpose to all writers. I think the broadest standard to which we hold ourselves should be to do the difficult part. There’s always a space in our work where we want to flinch and look away, or a draft we want to call good enough when we know it’s not, and I think our job is to make sure we don’t stop there, that we get all the way to the center of the thing that hurts, that we keep trying for the thing that’s hard to say or the words that are best for saying it. Our responsibility is, I guess, not to be cowards, but bravery on the page can mean a lot of things.

Danielle Evans’ reading and book signing will be held at 7 p.m., Jan. 31 . in O’Shaughnessy Performance Space.

This interview has been edited for style and clarity.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks