The full moon was just breaking through the clouds Sept. 28 when the Indigenous Cultures Club gathered on the Quad. Organizers say they were there to do what Native Americans have traditionally done for centuries; to gather and tell stories. Seated in a circle, one by one attendees shared tales from their lives and ancestors’ lives well into the night. Some told stories more than 150 years old while others shared tales from just a few years, months or weeks back. It didn’t matter what the nature of the story was. The point of the gathering was to connect with others. The Indigenous Cultures Club was created last year when it became apparent that there were a lot of Native American students on campus but very few were talking to each other. “We kind of kept to our own cliques,” Treasurer Raven Two Feathers explains. There wasn’t a space for Indigenous students to talk about culture on campus, she says, so, “We saw a hole and decided to fill it.” Not long after, the ICC was formed and has been holding gatherings such as the Full Moon Gathering and last year’s Cultural Gathering ever since. Vice President Hallee Fresco and Two Feathers feel very passionate about The Full Moon Gathering. “The full moon is a time to cleanse,” says Fresco and added that traditionally gatherings such as these takes place in accordance with the lunar cycle. For many attendees, the event was a good way to get things off their chest. For one particular storyteller, the night was more than just a cleansing. Anna C Evanitz told a very old Croatian tale about her great great grandfather and how he died of literal laughter. After getting between two men in the middle of a fight, he received an axe to his chest. Luckily for him, the town’s doctor was in the same pub at the time and he survived. They stitched him up and a week later he was back in the pub with his friends. Unfortunately, the group of men began laughing so hard about the whole ordeal that Evanitz’s ancestor spilt his stitches and bled to death. “My father told me the story when I was a little kid,” Evanitz says. “It reminds me that my family is tough but also has a positive outlook on things.” She wants to adapt the story for film. “I tried to make it before but it came out too depressing. It’s supposed to be a funny story!” Evanitz says that she has told the story before in ICC and it always gets a good reaction. She enjoys sharing the tale even though it doesn’t come from Native American culture, which ICC fully supports. “Stories are important to pass on experiences from any culture,” says Two Feathers. She believes that whether one is native or not, it’s important to share your past. “Telling stories orally helps you hear someone’s individual voice in a different way than writing or film,” Two Feathers says, which is why she thinks gatherings such as these are so important. They give storytellers a greater means of sharing not only their experiences, but a little bit of themselves as well. It’s more intimate to sit in a circle with a group of people than to send a manuscript to a stranger to read. The ICC hopes to continue holding storytelling events every month on the quad during the full moon. They are also planning to show Native American themed films during the new moon and are taking suggestions for films now. Regular club meetings are on Sundays in the Film School at a time to be announced. Those interested can learn more by joining the SFUAD Indigenous Cultures Club Facebook...

Q&A: Lobsang Tenzin

posted by Adriel Contreras

“Listening to that music, I have a scene playing out in my head.” Lobsang Tenzin regards the pianist who has been playing at Iconic Coffee brewery. We sit down to speak about Tenzin’s life and I learn about Tenzin, passionate storyteller. “I am always listening and imagining the stories with music in my life,” he says. “Even the birds or the leaves blowing make up scenes.” Tenzin was born in Lhasa, the capital city of Tibet. He fled from his country in order to escape the tyrannical government that offered very little freedoms for its people. “Both my parents were activists and I was too. I got in a lot of trouble,” Tenzin says with a smile. “People always say that Tibet is so beautiful as a landscape, as a people and as a culture. But the inside is so sad. There is no human right, no religious right, no educational rights and it’s so hard. I had to escape from Tibet. It is impossible to go back.” He ended up fleeing the country, and is now studying film at SFUAD after transferring from the Portland Community College with a bachelor’s degree in Integrated Media. Tenzin received SFUAD’s 2014 Unique Voice Scholarship through the Robert Redford/Milagro Initiative scholarship program. Jackalope Magazine: What does film mean to you? Lobsang Tenzin: For me, it’s more like a tool or a weapon in order to tell my people’s culture and stories. Now these days, all the older people from the older generations, they are wrinkled and dying, I want to keep all the wrinkles and grab all the stories that they have as much as possible. I can make short films and documentaries for the next generations; even if they don’t see these people, they will know their stories. It just keeps on passing; it must never vanish. JM: How would you define your style? LT: I’m like a Marine, and I think of myself like a sniper. My job is to shoot. I always shoot, even when I’m not working. I’ll shoot the leaves moving in the grass. I build up all the different shots and store them so I don’t have to go looking every time. If I want to make a small story I can just use the shots I already have. I can pick anything when I work. JM: Have you considered what exactly you want to focus on in the film school? LT: For me, it’s about the images. I want to be a cinematographer. But the way I see it, if I want to be a chef, I start from the dish washer. I need to understand how everything works. This semester I’m not taking any big production classes. I’m just taking some normal classes in order to understand this university. I don’t want to get too stressed out this semester. I am taking Native American Arts and History of Contemporary Art. JM: Can you tell us a little bit about how you came to this university in particular? LT: I was still studying at my other college in Portland. One of my professors asked me if I wanted to act. She introduced me to the director and he said I was perfect for the cast. They offered to give me acting classes for one year, Meisner acting classes to learn to work in front of the camera. I learned so many things. So basically I was always behind the camera and now I’m facing the camera. You have to give the perfect shot. So I was doing that while in school and the director of the film asked what I had planned once I graduated with an Integrated Media degree. He told me to look at Santa Fe University of Art and Design. He gave me the information and he even contacted the school for the Robert Redford scholarship. I then got my portfolio together, all...

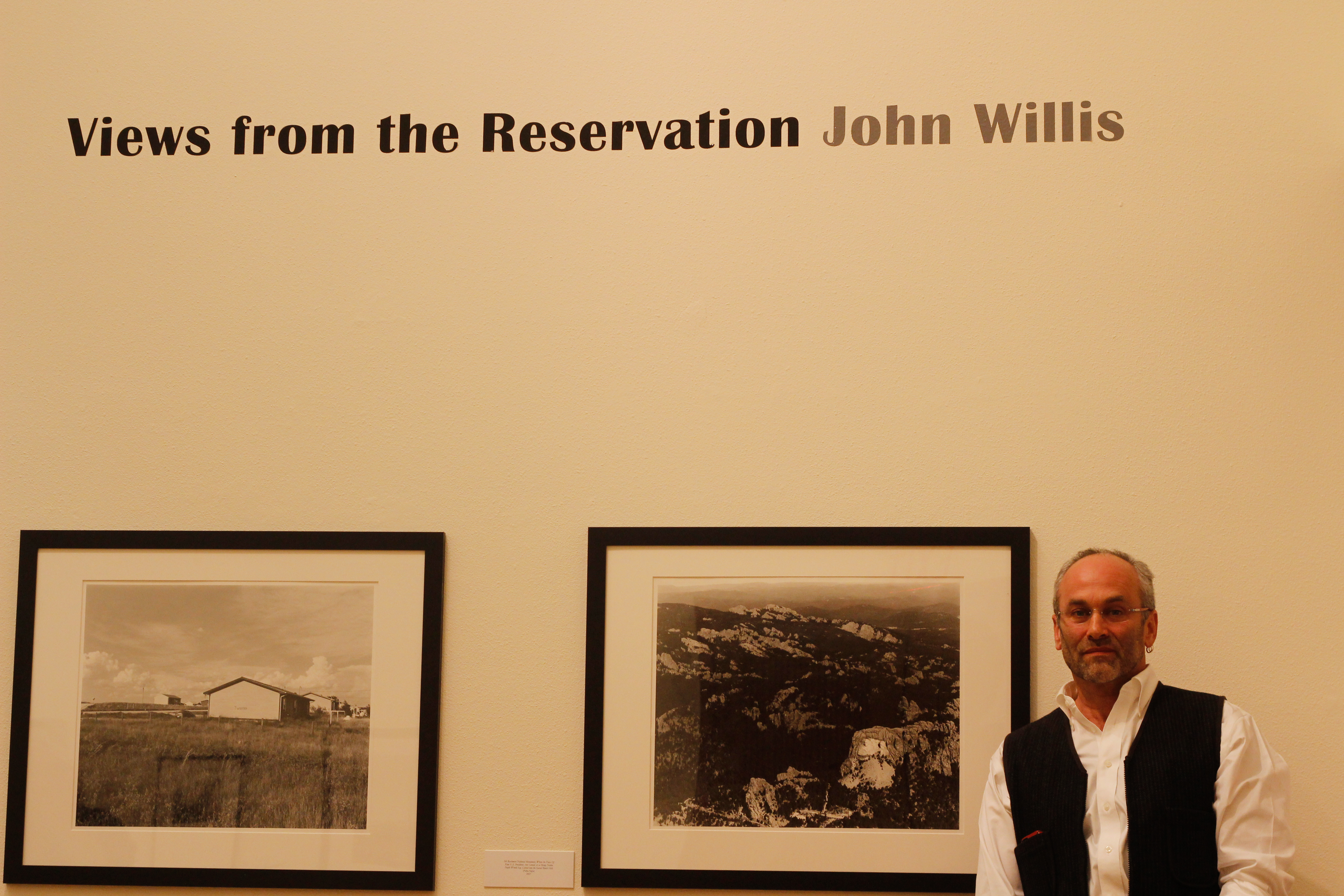

John Willis: Storyteller...

posted by Amanda Tyler

John Willis does not consider himself a photojournalist, or even strictly a documentary photographer. Willis, who teaches photography at Marlboro College in Vermont, has collections of work that would be hard not to coin as documentarian, but he sees a distinct differences between the types of storytelling that photographers can do. “There are a lot of ways to experience and to explore storytelling,” he explains, “and for me, it is always connected to something I’m experiencing—I choose my topics out of a need to work through my own stuff emotionally.” At the same time, Willis is acutely aware of the responsibility that comes with storytelling—perhaps even more so than many journalists. While he takes his pictures “to understand how I feel about things in my life,” Willis believes that, “if you are taking pictures of somebody, telling stories about somebody, you are an outsider, because it is not you that the story is about.” As an outsider telling somebody else’s story—or taking a photograph of somebody else—you have a responsibility, Willis believes, to that subject. You are responsible for telling their story to the best of your ability, honestly and respectfully, so that ultimately you will help others develop an empathic understanding of that subject. For Willis, this extends even further than just sharing his own photographs. For Willis, the difference between a journalist and a documentarian boils down to time. A documentarian affords themselves more time with their subject, something a journalist being paid by the story may not be able to do. “I have the luxury of making my images because they’re what I’m drawn to,” Willis explains, “because I make my living as a teacher.” When Willis sells an image, he thinks of it more as “extra-credit” than another step along...

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments