Tags

Related Posts

Share This

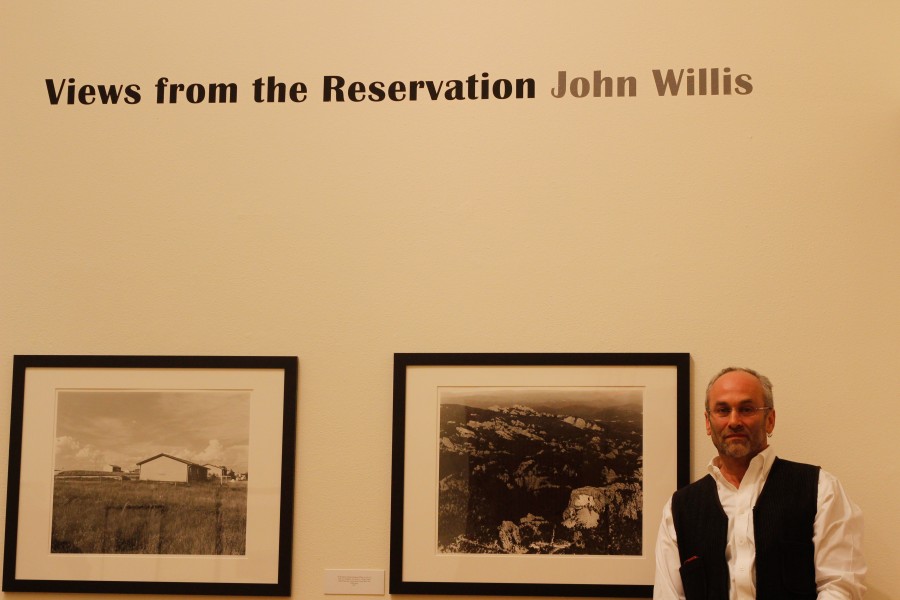

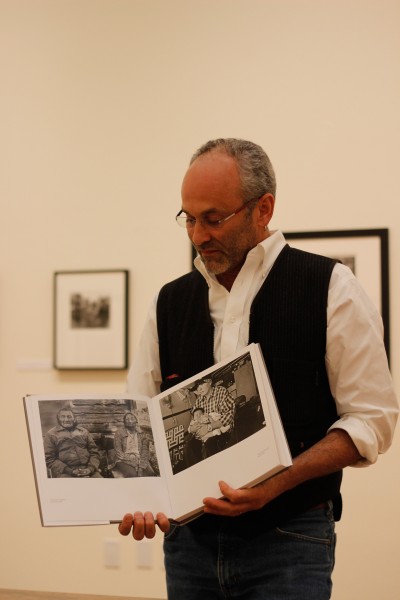

John Willis: Storyteller

John Willis does not consider himself a photojournalist, or even strictly a documentary photographer. Willis, who teaches photography at Marlboro College in Vermont, has collections of work that would be hard not to coin as documentarian, but he sees a distinct differences between the types of storytelling that photographers can do. “There are a lot of ways to experience and to explore storytelling,” he explains, “and for me, it is always connected to something I’m experiencing—I choose my topics out of a need to work through my own stuff emotionally.”

At the same time, Willis is acutely aware of the responsibility that comes with storytelling—perhaps even more so than many journalists. While he takes his pictures “to understand how I feel about things in my life,” Willis believes that, “if you are taking pictures of somebody, telling stories about somebody, you are an outsider, because it is not you that the story is about.” As an outsider telling somebody else’s story—or taking a photograph of somebody else—you have a responsibility, Willis believes, to that subject. You are responsible for telling their story to the best of your ability, honestly and respectfully, so that ultimately you will help others develop an empathic understanding of that subject. For Willis, this extends even further than just sharing his own photographs.

For Willis, the difference between a journalist and a documentarian boils down to time. A documentarian affords themselves more time with their subject, something a journalist being paid by the story may not be able to do.

“I have the luxury of making my images because they’re what I’m drawn to,” Willis explains, “because I make my living as a teacher.” When Willis sells an image, he thinks of it more as “extra-credit” than another step along the way to paying his bills and making a living.

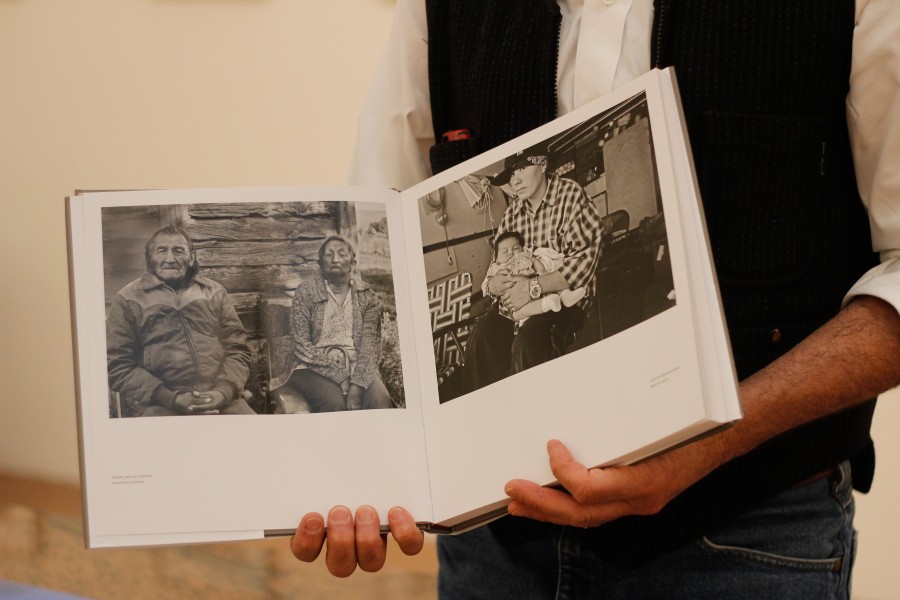

Time is an essential element in Willis’ process. His project Views From the Reservation, which amalgamated into a book in 2010, was an eighteen-year process that began without the intent of “doing a project.” Willis was invited onto Pine Ridge Reservation, home to the Oglala Lakota Sioux People, by an elder, Grandfather Eugene Reddest. Willis spent a summer there, photographing the landscape but never the people. On his last day there, he asked Reddest to sit for a portrait. Reddest agreed, and posed for a photograph with his adopted daughter. Willis, always intent on giving back to the subjects of his pictures, went home and made 30 prints of the portrait to send to Reddest for him to share with his family.

Willis was invited back to the Reservation the next year, and was gradually asked by more and more people to take their portraits. This continued for years, with Willis never taking a picture he wasn’t asked to take unless it was a landscape shot. Eventually, Reddest told Willis that he should think about some way to use the pictures that had been piling up for years in a way that would help the people of Pine Ridge. Willis began to hatch ideas for a book, which Reddest agreed to, so long as it contained the voice of the people. “The responsibility of telling these people’s story was given to me,” explains Willis, “and it took another two years for me to figure out how to do that.”

Willis eventually conceived of a plan that adhered to his philosophy of having a collaborative relationship between storyteller and subject; he gave the people of the reservation 75 packages each containing a point-and-shoot camera, a roll of film, and a pre-stamped addressed envelope for them to send the film back to him to be developed. On subsequent trips Willis collected poems, songs, prayers—whatever the people thought represented their own voices—consistently checking with the elders what was or wasn’t appropriate for him to include in his book.

For Willis, telling another person’s story is about helping others to see in a new way—helping people to understand how we pass judgment on each other. Through the photographs he takes, and the chances he offers his subjects to turn the lens on their own lives, he has certainly fulfilled the role of a storyteller, even a documentarian, as outlined by himself.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments