Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Black History Show Auditions

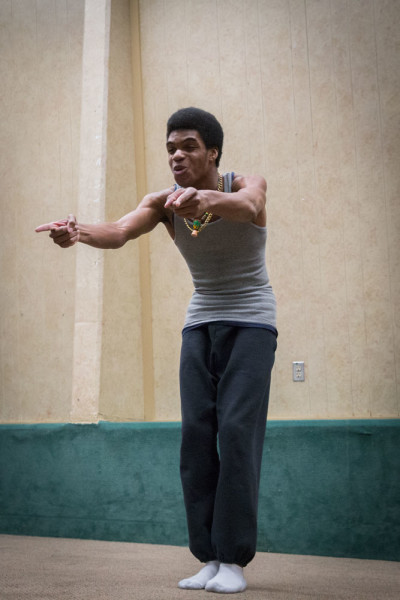

Watching SFUAD students audition for the Black History Show, one can’t help but have an immediate reaction. The sounds are diverse and heavy with meaning. Whether it’s singing, rapping or playing an instrument, the individuality of each performance can be heard.

“We’re looking for students that can encapsulate our entire history. Go all the way back to the roots; Negro spirituals and bring it back to who we are today. We want to have a wide range of musical talents,” says Ryan Henson, the Black Student Union advisor. In preparation for the actual event, which will take place in the 7-9 p.m. Feb. 20 in the Forum, the Black Student Union committee evaluated a series of performances by SFUAD students who auditioned on Feb. 5.

One of the first to audition, Josiah St. Lewis-Noray starts at the very foundations of African music by playing the djembe. This type of African drum is played with the hands and is built from animal skin and wood. From the very first beat, the echo reverberates in the body. The rhythm starts off slow and then builds to a point where it seems like there’s nothing else to do but dance. Then, just as abruptly as he began to play, St. Lewis-Noray stops. The rest of the students hoping to be a part of the Black History Show stop nodding and tapping to the beat and applaud.

“Mostly it’s just fun,” St.Lewis-Noray says about the upcoming student show, “but it’s also a way to share information about black culture; something positive.”

After his drum solo, the audience is catapulted into more contemporary music through renditions of songs by Etta James and Whitney Houston. Julaine Williams imbued the lyrics to “At Last” by Etta James with her own meaning. “My grandmother just passed away and Etta James is someone she really enjoyed listening to,” Williams says “Besides me, my grandmother is the only other singer in my family, so I wanted to dedicate the song to her.”

A pattern emerges in the responses of all the students auditioning. Through the opportunity the Black History show presents, students are able to relate and pay homage to an entire history of the evolution of sound that their culture developed. “I feel like black history month is something that is slowly becoming less important,” Williams says. “We have to understand why as a culture and as a race we’re able to get so far as a community. This history is a part of who I am. I can’t deny the color of my skin or that my talent comes from the people before me. It’s in my blood, it’s in my body.”

Brianna Pitts, who sang Whitney Houston’s “The Greatest Love of All,” also talks about how culture and music intertwine. “It’s empowering when black people stand up. You’ve got a lot of expectations. My color is a set off and I want to break through that barrier. People can feel us when we sing and when we do anything because we have so much heart. We are still underrated and underestimated.”

Eugene Mason the fourth, also known as G-4, and his African name Toumani, rapped the cover of musician Kendrick Koulmar’s untitled song. “I’m a lyricist so when I hear a conscious influential message through spoken word and rap it inspires me. I hope the audience can see more than just a black guy rapping,” Mason says. “I hope they see somebody who has a vision, someone who has a message. As black people we are more than what the media tells us we are. We can use words to inspire people beyond the status quo.”

After the auditions are over, the Black Student Union committee goes over the individual performances and decides who will be performing at the actual event. While evaluating both the sound and stage presence of those who auditioned, Tikia “Fame” Hudson, BSU vice president, talks about the aim of The Art of Liberation: A Black History Show. “When artists think of a show we think of music and singing. It’s the most relatable medium; we want to fall in love with the beat and the stage presence,” Almost all of the students’ performances are based off of rhythm or sound. The numerous musical auditions aim to express African American culture and history through their instruments and voices. “Our ancestors communicated through hymns and Negro spirituals; it was their own secret language, like a code only they understood,” Tikia Hudson explains. “Today, we want to let people know we haven’t always had claim to everything. We want to encourage people to explore more of our music. To think ‘Black music did this. Let me hear more of this music.’ I definitely think this is what this show aims to do.”

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks