Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Burning Trees to Save the Forest

Late last week, white smoke plumed from the eastern Sangre de Cristos, the result of a three-day prescribed burn just north of the McClure Reservoir in the privatized watershed.

Burning dead and down tree by the McClure Reservoir. Photos by Brantlee Reid

It’s easy to assume the opaque clouds rising from the mountains is a tragedy, a massacre of nature, an act of deforestation. “It’s a common misconception,” Forest Service Assistant Public Affairs Officer Cliff Russell says. The white smoke you’ll continue to see over the next week actually indicates a slow, steady, smoldering burn that is mostly comprised of steam. “When people think fire, they think that we’re killing every single tree and that it’s like a forest fire, raging through and leaving behind toothpicks, but that’s not what we do.”

Santa Fe National Forest Hotshot Superintendent David Simpson navigates the smoldering mountainside.

The low-intensity burns are a part of a colossal interagency project that aims to preempt catastrophic wildfires in particularly susceptible environments, especially in areas that require protection from external threats such as the watersheds. “The whole goal of prescribed burning isn’t to kill the trees but to recycle all the dead stuff that has fallen: pine needles, pinecones, rotting trees,” Russell says. “It releases nutrients into the soil and makes for a clean forest floor.” If a high-intensity fire were to sweep through the watershed during a dry summer in an untreated area, it would burn so large and hot that the soil would be consequentially destroyed, causing a vast amount of land to be uninhabitable for new growth for a couple of years afterward. Come monsoon season, the rains would wash leftover ash and dead trees into the water, tainting the Santa Fe River and watersheds.

The lightening-triggered McClure fire earlier this year is an example of the profitability of prescribed burns. Since the ground fuel was minimal due to previous treatments, it only maximized to 7.6 acres before fire officials achieved 100 percent containment.

Area before a prescribed burn.

Prescribed burn one year later.

Unfortunately, we didn’t always have the understanding of our environment that we have now. According to the Fire Service Federal website, in 1935, “the Forest Service had a “10 a.m.” policy which stipulated that a [naturally caused] fire was to be contained and controlled by 10 a.m. following the report of a fire, for, failing that goal, control by 10 a.m. the next day and so on.” This readiness to blanket natural wildfires resulted in the overgrowth of vegetation and thusly the unemployment of weather itself from proceeding with the grooming necessary for a healthy and balanced environment. “Fire is a part of the natural ecosystem of the forest,” Russell says. “Because we took fire out of the ecosystem, we are now having to go back in and start to thin out the forests and reintroduce it.”

Jana Comstock consults with Cliff Russell

And the Forest Service takes every precaution when doing so. After weeks of extensive surveying of the reservoir for promising flammable features such as low levels of fuel moisture, permission was finally granted on Oct. 12. “Measurements are taken beforehand, during, every hour on the hour to make sure that it’s still ripe for burning,” archeologist Jana Comstock says.

This burn was initially postponed earlier in the year due to unfavorable conditions: scaling heat, dehydrated terrain and winds that refused to let up, circumstances under which a fire can quickly become riotous, as with the Cerro Grande fire in May of 2000. What started out as a prescribed burn at the Bandelier National Monument quickly escalated to an unruly rampage and the

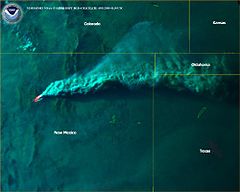

The Cerro Grande plume on May 11, 2000, reaches the panhandle of Oklahoma (NOAA image) via Wikipedia.

decimation of approximately 48,000 acres because of spontaneous winds. “It’s not worth the risk of something like that happening if the conditions aren’t within what you want them to be,” Russell says of the Cerro Grande fire. “We want to put the fire on the ground on our terms.”

Russell encourages anyone who opposes the fires to witness them firsthand. “We have an open invitation for anybody who is against prescribed burning to come out here and see what we do, during a fire, after a fire, whenever.”

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments