Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Wikswo Joins SFUAD

Quintan Ana Wikswo (Photo by Octavia Eduardo-Corral)

Santa Fe University of Art and Design’s list of faculty has changed dramatically since last school year. An exciting new addition, Quintan Ana Wikswo, joined the Creative Writing and Literature department over summer and is currently teaching classes in both literature and fiction for the fall semester. Working in multiple mediums besides writing , such as film, photography and live performance, Wikswo has more than 35 published projects under her belt. From magazines and anthologies such as Tin House to solo museums exhibitions in New York and Germany, Wikswo’s work has reached audiences all over the world. She’s co-founder of the Spiderflower Collective, an intersectional arts and activism group in Santa Fe.

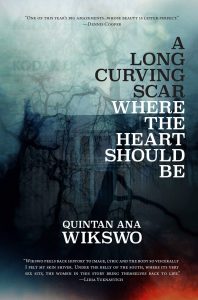

Wikswo utilizes both image and text in ways that speak to her central interests and passions, which lie in human and civil rights, silencing and secrecy. In her forthcoming novel, A Long Curving Scar Where The Heart Should Be, coming in 2017 from Stalking Horse Press (former Creative Writing and Literature Chair James Reich’s independent press), she writes about her methodologies. “By using cameras and typewriters from the segregation era at sites with contested or hidden histories, I attracted the attention of folks who realized the significance of those instruments in that particular timespace.”

Jackalope Magazine: When did you become an artist?

Quintan Ana Wikswo: I grew up in the extremely rural south… I had no formal education, I didn’t go to school until high school. So I don’t have a lot of familiarity with how the educational institution works. It was a shock to actually encounter things like grades and authority figures. I mostly spent time working with veterans of the [Southern Christian Leadership Conference] who were directly taught by [Martin Luther King Jr.], so that’s where my education came from all the way through high school. I was just following them around and they were still working on civil rights issues in all these little towns. So that had a huge impact. Then it took me about eight years to get my undergrad, as I went to seven different universities and I took a lot of time off working my way through. So I had a very non traditional undergrad. Never taken an English class, never took a creative writing class, and all I really cared about was civil rights and human rights and activism and gender rights.

When I finally found the mentor who changed my life, Dr. Robin Kilson, who passed away a few years ago of MS (had been a Black Panther), she said that while I would always be an activist, I should actually write because I had a gift with language. It was astonishing to me because I didn’t think anything that I said was ever even listened to. So she kind of picked me up one day after class with her car and a case of champagne and said that I was going to stay at her house until I had written three short stories, and we’d finish the champagne. And then I said I’d never written a short story before, and she said ‘I don’t care.’ So I gave her, at the end of it, my three pieces, and without me knowing she sent them to MFA programs for creative writing. So I went to San Francisco State to do hybrid poetry and fiction. I was primarily doing human rights work, and not any art work, until about seven years ago. When I decided I wanted to speak for myself instead of speak for an organization.

What mediums do you work in?

I work with image making, photographers don’t consider them photographs. I use salvaged, broken, old cameras and I adapt them. So I do conceptual photography and conceptual filmmaking and video making, some of which are just incredibly boring endurance exercises. And some are videos of my performance pieces at the sites where I work. So I also do solo performance work, and I do performance collaborations with composers and choreographers.

Why do you feel it’s necessary for you to work in so many different artistic areas?

I’m horrified by categories. I’ve never personally, as a human creature, fit into a category, and my education was never putting things into categories in terms of subject matter. Anything I’ve ever been interested in has been people and situations that are not easily categorized. Ideologically, I oppose categories. I like looking at things from lots of different perspectives.

I like making mistakes and being messy. It was really important to me to be working in art forms that I couldn’t really master. I have always had, apparently, a gift with language, but I’m not a natural performer in the slightest. And the things that emerge by doing that make me grow in ways where I would just be like…‘yeah, man I can write…’

Also, I think it’s primarily been that there are police that are monitoring every discipline very, very strictly. And basically as soon as the police get on me in one discipline, I want to be able to move to the other. When I work in photography, it’s a matter of time until a bunch of people come and say, ‘you’re breaking this rule, you can’t do this’ etc. and then I can switch over. And part of it is for my own mental health, because I don’t want to be told what I can do, but a lot of it is that I couldn’t get – the novel that’s coming out – I couldn’t get the literary community to deal with the subject matter, but if I put it with photographs, I could get the visual art community to deal with the subject matter. So a lot of it is trying to be heard, and it gives me a broader range of audience, so somehow this will get out.

Wikswo’s forthcoming novel “A Long Curving Scar Where the Heart Should Be” (Stalking Horse Press, 2017)

You said you like to be messy, what do you think about “perfect” art?

I’m hostile toward and suspicious of anything that’s held up as “perfection.” Because I think that our society is so sick that what we have been taught is perfection, is actually quite frequently a virus, an illness. So if we get hung up on perfection, there’s something that’s very eugenics-based about that. Who decides what’s perfect? Who decides what’s imperfect? And why should only the perfect live? I mean, should only the perfect person live? Well no, only a monster would say that. But somehow in the world of art, especially the world of literature, there’s the idea that only the perfect text should be revealed. This yields sanitized texts. It yields a normalcy and a homogeneousness, and as a writer it doesn’t serve us because we can’t grow. Waiting for a magical point where you and your work are considered perfect enough to be seen is fascist.

What environment do you want in your classrooms this semester?

I think our culture, social as well as political and artistic, has been defined by silence and silencing. I’m excited for a new generation of writers to be self-liberated from those constrictions that have plagued us old folks for a long time. So, in terms of the classroom, I think it matters to me that folks are given the tools that you need to maintain a level of confidence, excitement and power to write for yourself and write your actual truths for the rest of your life. It’s not a matter of stopping this semester or stopping at the end of school. It’s how you develop the core character to be a lifelong writer and be confident enough to fully embody self expression and feel unlimited by anything that you want to say. To feel that you have no limitations on being able to speak and say and write whatever it is that you need to, from now until you’re 150 years old.

Have you noticed anything specific about your artistic process?

It helps to have enemies. I think I write for retribution, vengeance, emotional reparations. I’ve been thinking a lot about emotional reparations and emotional justice because there’s no real money in writing, so those of us who are pursuing it as an art form are doing it for other reasons. I’ve been thinking a lot about what my other reasons are. And I think I am very driven by the need for emotional reparations from history, from this society, from specific people in my life. But every book that I have written has been written around real violence…I think there has to be a lot at stake in order to sustain the drive to complete a project.

I think an adversary is different than a hater. An adversary, to me, is the force that I’m pushing against, it’s the silencing force. It’s not so much that I write in anger, it’s that I need to feel something pushing back at me and feeling that I’m pushing at something. And then there’s a relationship. It’s not just me throwing into the void, the void is writing back to me, is talking back to me as I’m talking to it. So I have to feel that there’s a conversation with the larger cosmos happening.

Any reading you would recommend right now?

Oh, there’s so much. Everything by Audre Lorde. In general, I would say go deep. The books that you’re hearing about are the least interesting because they have the broadest possible appeal. So they’re taking the fewest chances. So…indie presses! I think the best writing is the writing that reminds us to be fierce because we need reminders of that as often as possible, or at least I do, to have reassurances that fierceness is vital when we get much more messaging that we ought to be obedient and likeable.

Notebook of a Return to the Native Land by Aimé Césaire is my favorite book ever. It’s also very timely because I think reading under a dictator who’s taken power through a coup makes it important as writers to see what may be coming down the pipeline, and what it takes to write against a leader who wants almost all of us dead. So the literature that I’m most interested in are things that will help me survive.

What has your experience at SFUAD been like?

I’ve never been interested in a career in academia…and the students here have been, at least in my classes, my favorite anywhere I’ve ever taught. Far and away. You guys have a lot of fight in you, and I think you’ve been given a really raw deal, and unfortunately that’s the world. So instead of having this period of time that a lot of college students have where you have this idea of the rosy little world and then you leave college…you guys are having to face some really challenging barriers at a time when a lot of your peers wouldn’t have to be. But your responses have so much strength, especially the ones who are still left, the amount of passion and determination…that’s what it takes to still be writing in 80 years. What I see in you guys is a lot of people who have the ability to be writers on the long haul, not just in school. So I feel really fortunate to be here. I mean, I’m writing more recently, because I’m excited by what comes up in class. If my students provoke me to write, there’s no higher compliment. You all inspire me and I come home and I want to write? These are the best students ever.

This interview has been edited for style and clarity.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Recent Comments