Tags

Related Posts

Share This

Elegy Made Manifest

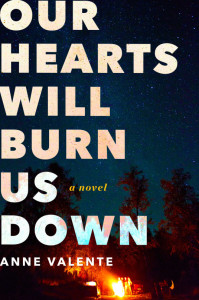

With the close of September, Anne Valente’s debut novel Our Hearts Will Burn Us Down approaches its release date. A local school shooting leaves a St. Louis community reeling, especially high school juniors Matt, Zola, Nick, and Christina. The four main characters struggle to piece their lives back together and make sense of the tragedy while a series of fires continues to ravage the homes of victims’ families. Ultimately the story within is a stunning tale of the all-consuming nature of grief and the permanence of loss, in and of itself a statement about a society where mass violence is increasingly common. Originally from St. Louis, this will be Valente’s second year teaching in the Creative Writing and Literature department at SFUAD. Jackalope Magazine sat down with Valente to discuss her upcoming book and her journey to publication.

Creative Writer Anne Valente. Photo by Sasha Hill.

Jackalope Magazine: You’ve previously published the chapbook An Elegy for Mathematics and the story collection By Light We Knew Our Names, but this is your first novel. How did the publishing process differ?

Anne Valente: It was a much more involved process. The chapbook — I was contacted by the publisher to see if I had any flash fiction, who had read some of my shorter pieces, so that was a relatively easy process. And the short story collection — I had put together a collection, and since there’s less of a market for short story collections, I sent that out to contests, and eventually, won a book contest. Once the short story collection came out, that book attracted the attention of an agent, and… that’s what I needed to publish a novel. So she started sending the book out. It took about three months to find a publisher. And since then, the past year and a half has been editing, shaping up the manuscript with agent and editor. All three of those [processes] have been very different, but very good processes.

What is your favorite part of the publishing process?

Beyond an actual tangible favorite part of that process, I actually think the less tangible side of it is my favorite part — just having this small team of people who really cares about your work and really believes in what you’re doing, knowing that there are people who understand what you’re trying to do, and they’ll put it out there.

How did the story come together for you? Was it inspired by anything in particular?

I’d written only short stories and had never tried to write a novel. It just seemed way too daunting. I had been working on short stories at the time about St. Louis. Like, “I’ve spent enough time not writing about where I’m from, so I’m going to write some short fiction about my hometown.” And I was two stories into that when the shooting at Sandy Hook happened. This was December of 2012. So I started writing a short story that was just in response to that. The short story ended up seeming like it was not enough — it was a short story by the same name as the novel — and I didn’t think I would be a writer that would turn a short story into a novel, but that’s what happened. It just seemed like there was a far larger narrative there to work with. The story was initially about elementary school children, and for the purposes of a novel, to help explore those characters more and give them more of a backstory, I made it into a story about a high school shooting.

The book is written in the first-person plural perspective. Was that also present in the short story?

It was, yes. I’m drawn to that point-of-view, and it’s been easier to manage in a short story. But I found that I wanted that… in the novel, but that it would become possibly cumbersome for the reader to make every single section in the collective first-person, so I did splinter off into four third-person sections for each of these characters and developed them. I think the reason I was drawn to this [first-person plural] is my reaction as a human being to the Sandy Hook shooting, to many of these other instances of gun violence that we have in our culture. I feel devastated by this, but I also know this is not necessarily my grief to experience. It is and it isn’t; it’s our national culpability and our national grief to mourn, but it’s very different if you lost someone in one of those shootings. I think that’s why I took that point-of-view. [I was] interested in that tension of what is ours collectively and what isn’t ours at all.

‘Our Hearts Will Burn Us Down’ will be released on Oct. 4, 2016.

The book takes place in October 2003. How did you envision the political backdrop resonating with the immediate tragedies in the book?

It seems like we have weekly mass shootings now, and we have this huge social media presence of sharing that information, so I was drawn to a period of time when we hadn’t grown so numb to it. I ended up being more drawn to [2003] because of all the things that were happening in politics and the world at that time. The weapons of mass destruction search was heavily underway at this time, and… that backdrop now feels like it’s so focused on this need for answers and this need for certainty, especially after 9/11. That felt like a foil for what these characters are experiencing, of needing an answer for grief when there sometimes aren’t answers for those emotions.

How do you see it resonating with current events?

I finished this novel in June or July 2014, and then in August 2014, Michael Brown was shot and killed in St. Louis, which… changed my entire view retrospectively of this narrative and what violence means, but also of my hometown. They all seem to be part of the same conversation of gun violence, of mass violence, brutality and police brutality. I maybe naively thought that by the time this book was published, we would have some kind of answer to gun legislation or gun violence, and it just seems like this has been one of the most violent years on record. I hope this book can be part of this conversation in some way that doesn’t feel exploitative, [is] able to engage with violence in some way that pushes the conversation forward.

What was your favorite part of the book to write?

I don’t know if “fun” is the right word. To tie things up in a way that doesn’t necessarily tie things up was “fun” for me to write… because the last section moves around in time, moving between reviewing this actual shooting and then having a scene of these students attending their homecoming dance. Playing with point-of-view and playing with time in that section was “fun” to write. It was obviously devastating to write, too… but in terms of being able to manipulate those aspects of craft to better serve the purpose of the narrative, [it] was illuminating, as a writer.

Was there anything about the book you only learned about after finishing? Themes, symbols, etc.

One small thing that I’ve taken note of is this notion of people combusting inside of their homes feels very Midwestern to me. Midwestern people just don’t talk about their feelings, in general. Obviously in a very different way, but if these particular emotions have nowhere to go, in the privacy of your own home, it could end up combusting, I suppose.

Full-time Creative Writing faculty member Anne Valente discussing her novel ‘Our Hearts Will Burn Us Down’ which releases October 4th, 2016. Photo by Sasha Hill.

Were there any major decisions you made, plot-wise, that could have influenced how the book turned out?

Yeah, and some of that changed during the revision process. I think initially the notion of something… that’s not necessarily tangible happening in this community was revealed much earlier in the book. I think really, I didn’t have something that I was writing towards. I was just figuring out this community and how they were dealing with grief as I went through the book. That’s still a tough thing about this book, is that I know, as readers, you want some kind of resolution, some kind of answer, even if you don’t necessarily care about the shooter. I know a lot of readers want to know why that happened, why a shooter did what he did, but I felt so resistant, as a writer, to offering those kinds of answers because I don’t want people to read for that. I just wanted to explore the after, in terms of what we don’t talk about as much.

Do you have any advice to aspiring writers?

I definitely feel like you should write your passions, the things that you are most excited about. I know that there are enormous pressures out there to write a certain type of work or follow marketing trends, and I wrote this entire book before I even had an agent and I had no idea if it would get published. Eventually, trying to just determine what makes you tick as a writer. I think… audiences can tell what’s you and what’s not you. Write what is you.

—

Anne Valente’s Our Hearts Will Burn Us Down publishes Oct. 4, 2016 and an on-campus reading will be held Oct. 18.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

Jackalope Magazine is the student magazine of Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Building on the interdisciplinary nature of our education, we aim to showcase the talent of our university and character of our city.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks